I. WELCOME

This may be the beginning of a grand adventure. Programming languages encompass a huge space to explore and play in. Plenty of room for your own creations to share with others or just enjoy yourself. Brilliant computer scientists and software engineers have spent entire careers traversing this land without ever reaching the end. If this book is your first entry into the country, welcome.

這也許是一場大冒險的開始。編程語言包含了一個巨大的探索和遊戲空間。在其中,你有足夠的空間與他人分享自己的創作,或者只是自娛自樂。傑出的計算機科學家和軟件工程師窮盡整個職業生涯都在穿越這片土地,卻從未到達終點。如果這是你第一次進入這個國度,歡迎你。

The pages of this book give you a guided tour through some of the world of languages. But before we strap on our hiking boots and venture out, we should familiarize ourselves with the territory. The chapters in this part introduce you to the basic concepts used by programming languages and how they are organized.

本書的內容為你提供了一些語言世界的導覽。但是,在我們穿上登山靴開始冒險之前,我們應該先熟悉一下這片土地。本部分的章節將向你介紹編程語言所使用的基本概念以及它們的組織方式。

We will also get acquainted with Lox, the language we’ll spend the rest of the book implementing (twice). Let’s go!

我們以後還會熟悉Lox,這門語言我們將用本書的其餘部分來實現(兩次)。讓我們開始吧!

1. 前言 Introduction

Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.

—— Neil Gaiman, Coraline

童話故事是無比真實的:不是因為它告訴我們龍的存在,而是因為它告訴我們龍可以被擊敗。

I’m really excited we’re going on this journey together. This is a book on implementing interpreters for programming languages. It’s also a book on how to design a language worth implementing. It’s the book I wish I had when I first started getting into languages, and it’s the book I’ve been writing in my head for nearly a decade.

我真的很興奮我們能一起踏上這段旅程。這是一本關於為編程語言實現解釋器的書。它也是一本關於如何設計一種值得實現的語言的書。我剛開始接觸編程語言的時候就希望我可以寫出這本書,這本書我在腦子裡已經寫了將近十年了。

In these pages, we will walk step by step through two complete interpreters for a full-featured language. I assume this is your first foray into languages, so I’ll cover each concept and line of code you need to build a complete, usable, fast language implementation.

在本書中,我們將一步一步地介紹一種功能齊全的語言的兩個完整的解釋器實現。我假設這是您第一次涉足編程語言,因此我將介紹構建一個完整、可用、快速的語言所需的每個概念和代碼。

In order to cram two full implementations inside one book without it turning into a doorstop, this text is lighter on theory than others. As we build each piece of the system, I will introduce the history and concepts behind it. I’ll try to get you familiar with the lingo so that if you ever find yourself in a cocktail party full of PL (programming language) researchers, you’ll fit in.

為了在一本書中塞進兩個完整的實現,而且避免這變成一個門檻,本文在理論上比其他文章更輕。在構建系統的每個模塊時,我將介紹它背後的歷史和概念。我會盡力讓您熟悉這些行話,即便您在充滿PL(編程語言)研究人員的雞尾酒會中,也能快速融入其中。

But we’re mostly going to spend our brain juice getting the language up and running. This is not to say theory isn’t important. Being able to reason precisely and formally about syntax and semantics is a vital skill when working on a language. But, personally, I learn best by doing. It’s hard for me to wade through paragraphs full of abstract concepts and really absorb them. But if I’ve coded something, run it, and debugged it, then I get it.

但我們主要還是要花費精力讓這門語言運轉起來。這並不是說理論不重要。在學習一門語言時,能夠對語法和語義進行精確而公式化的推理1是一項至關重要的技能。但是,就我個人而言,我在實踐中學習效果最好。對我來說,要深入閱讀那些充滿抽象概念的段落並真正理解它們太難了。但是,如果我(根據理論)編寫了代碼,運行並調試完成,那麼我就明白了。

That’s my goal for you. I want you to come away with a solid intuition of how a real language lives and breathes. My hope is that when you read other, more theoretical books later, the concepts there will firmly stick in your mind, adhered to this tangible substrate.

這就是我對您的期望。我想讓你們直觀地理解一門真正的語言是如何生活和呼吸的。我希望當你以後閱讀其他理論性更強的書籍時,這些概念會牢牢地留在你的腦海中,依附於這個有形的基礎之上。

1.1 Why Learn This Stuff?

1.1 為什麼要學習這些?

Every introduction to every compiler book seems to have this section. I don’t know what it is about programming languages that causes such existential doubt. I don’t think ornithology books worry about justifying their existence. They assume the reader loves birds and start teaching.

每本編譯器書籍的導言似乎都有這一部分。我不知道到底是編程語言的哪一點讓人產生這樣的質疑。我不認為鳥類學書籍會擔心如何證明自己的存在。它們假定讀者喜歡鳥類,然後開始教學。

But programming languages are a little different. I suppose it is true that the odds of any of us creating a broadly successful general-purpose programming language are slim. The designers of the world’s widely-used languages could fit in a Volkswagen bus, even without putting the pop-top camper up. If joining that elite group was the only reason to learn languages, it would be hard to justify. Fortunately, it isn’t.

但是編程語言有一點不同。我認為,對我們中的任何一個人來說,能夠創建一種廣泛成功的通用編程語言的可能性都很小,這是事實。設計這個世界上被廣泛使用的語言的設計師們,一輛大眾旅遊巴士就能裝得下,甚至不用把頂上的帳篷加上。如果加入這個精英群體是學習語言的唯一原因,那麼就很難證明其合理性。幸運的是,事實並非如此。

1.1.1 Little languages are everywhere

1.1.1 小型語言無處不在

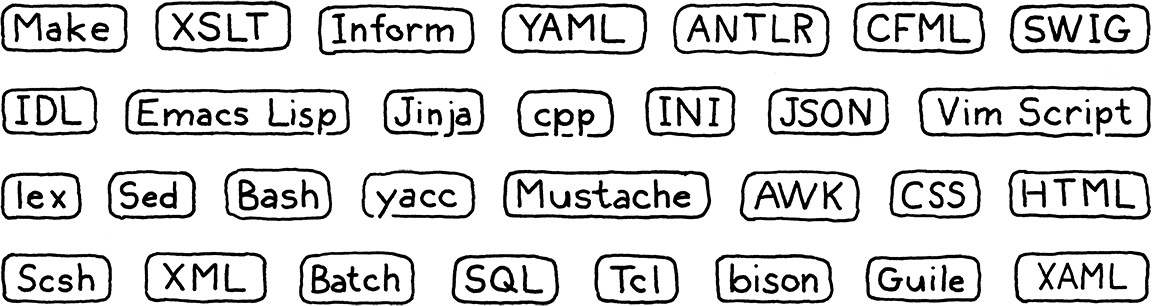

For every successful general-purpose language, there are a thousand successful niche ones. We used to call them “little languages”, but inflation in the jargon economy led today to the name “domain-specific languages”. These are pidgins tailor-built to a specific task. Think application scripting languages, template engines, markup formats, and configuration files.

對於每一種成功的通用語言,都有上千種成功的小眾語言。我們過去稱它們為“小語言”,但術語氾濫的今天它們有了“領域特定語言(即DSL)”的名稱。這些是為特定任務量身定做的洋涇浜語言2,如應用程序腳本語言、模板引擎、標記格式和配置文件。

Almost every large software project needs a handful of these. When you can, it’s good to reuse an existing one instead of rolling your own. Once you factor in documentation, debuggers, editor support, syntax highlighting, and all of the other trappings, doing it yourself becomes a tall order.

幾乎每個大型軟件項目都需要一些這樣的工具。如果可以的話,最好重用現有的工具,而不是自己動手實現。一旦考慮到文檔、調試器、編輯器支持、語法高亮顯示和所有其他可能的障礙,自己實現就成了一項艱鉅的任務。

But there’s still a good chance you’ll find yourself needing to whip up a parser or something when there isn’t an existing library that fits your needs. Even when you are reusing some existing implementation, you’ll inevitably end up needing to debug and maintain it and poke around in its guts.

但是,當現有的庫不能滿足您的需要時,您仍然很有可能發現自己需要一個解析器或其他東西。即使當您重用一些現有的實現時,您也不可避免地需要調試和維護,並在其內部進行探索。

1 . 1 . 2 Languages are great exercise

1.1.2 語言是很好的鍛鍊

Long distance runners sometimes train with weights strapped to their ankles or at high altitudes where the atmosphere is thin. When they later unburden themselves, the new relative ease of light limbs and oxygen-rich air enables them to run farther and faster.

長跑運動員有時會在腳踝上綁上重物,或者在空氣稀薄的高海拔地區進行訓練。當他們卸下自己的負擔以後,輕便的肢體和富氧的空氣帶來了新的相對舒適度,使它們可以跑得更遠,更快。

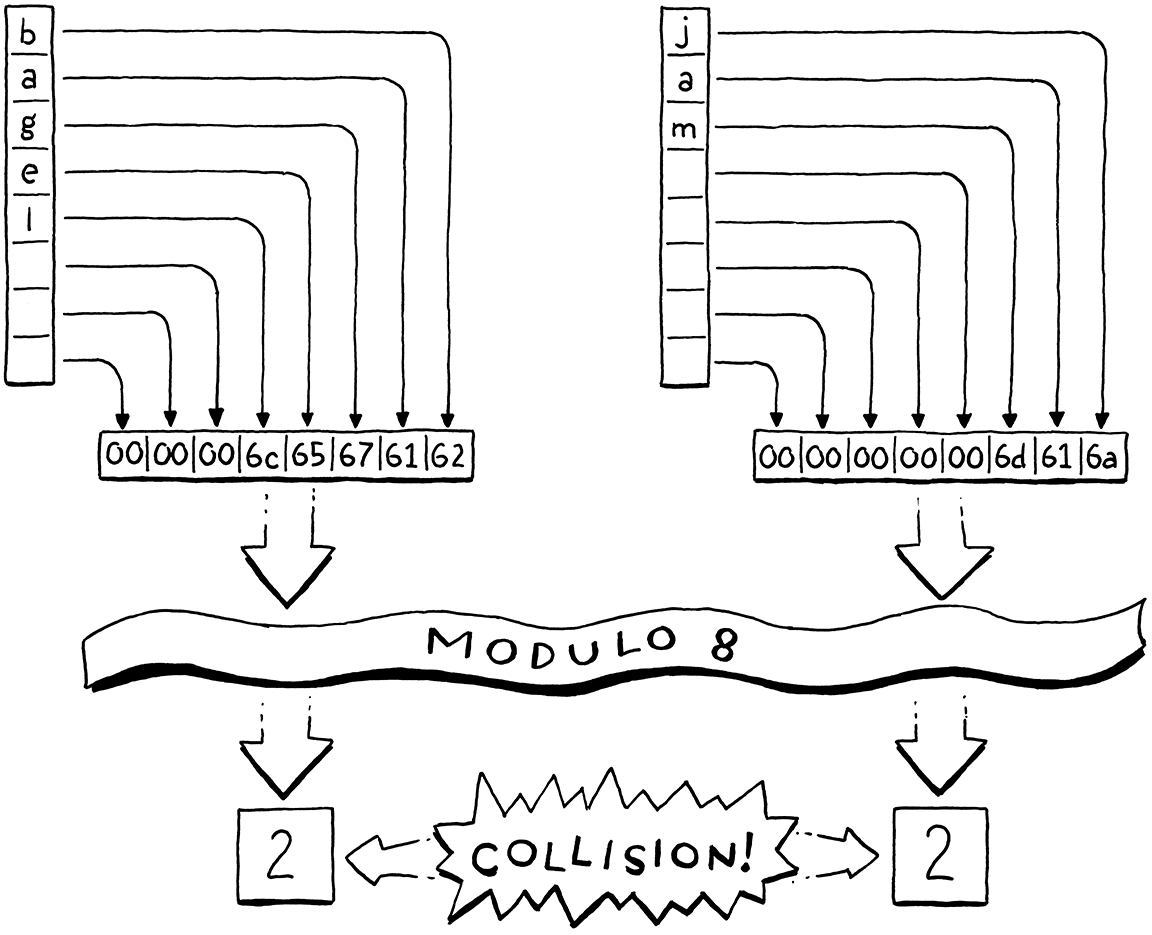

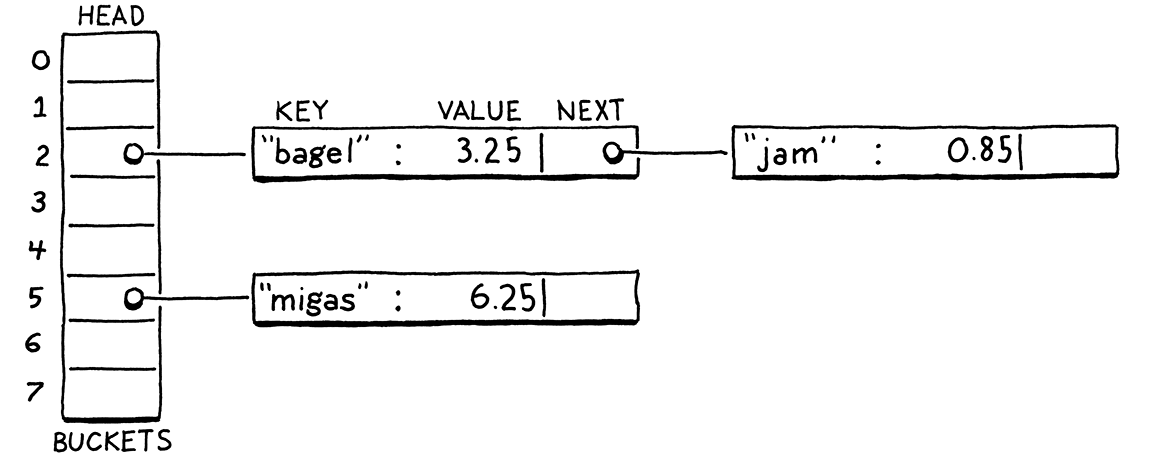

Implementing a language is a real test of programming skill. The code is complex and performance critical. You must master recursion, dynamic arrays, trees, graphs, and hash tables. You probably use hash tables at least in your day-to-day programming, but how well do you really understand them? Well, after we’ve crafted our own from scratch, I guarantee you will.

實現一門語言是對編程技能的真正考驗。代碼很複雜,而且性能很關鍵。您必須掌握遞歸、動態數組、樹、圖和哈希表。您在日常編程中至少使用過哈希表,但到底您對它們的理解程度有多高呢?嗯,等我們從頭完成我們的作品之後,我相信您會理解的。

While I intend to show you that an interpreter isn’t as daunting as you might believe, implementing one well is still a challenge. Rise to it, and you’ll come away a stronger programmer, and smarter about how you use data structures and algorithms in your day job.

雖然我想說明解釋器並不像您想的那樣令人生畏,但實現一個好的解釋器仍然是一個挑戰。學會了它,您就會成為一個更強大的程序員,並且在日常工作中也能更加聰明地使用數據結構和算法。

1 . 1 . 3 One more reason

1.1.3 另一個原因

This last reason is hard for me to admit, because it’s so close to my heart. Ever since I learned to program as a kid, I felt there was something magical about languages. When I first tapped out BASIC programs one key at a time I couldn’t conceive how BASIC itself was made.

這最後一個原因我很難承認,因為它是很私密的理由。自從我小時候學會編程以來,我就覺得語言有種神奇的力量。當我第一次一個鍵一個鍵地輸入BASIC程序時,我無法想象BASIC語言本身是如何製作出來的。

Later, the mixture of awe and terror on my college friends’ faces when talking about their compilers class was enough to convince me language hackers were a different breed of human—some sort of wizards granted privileged access to arcane arts.

後來,當我的大學朋友們談論他們的編譯器課程時,臉上那種既敬畏又恐懼的表情足以讓我相信,語言黑客是另一種人,某種可以操控奧術的巫師。

It’s a charming image, but it has a darker side. I didn’t feel like a wizard, so I was left thinking I lacked some in-born quality necessary to join the cabal. Though I’ve been fascinated by languages ever since I doodled made up keywords in my school notebook, it took me decades to muster the courage to try to really learn them. That “magical” quality, that sense of exclusivity, excluded me.

這是一個迷人的形象,但它也有黑暗的一面。我感覺自己不像個巫師,所以我認為自己缺乏加入秘社所需的先天品質。 儘管自從我在學校筆記本上拼寫關鍵詞以來,我一直對語言著迷,但我花了數十年的時間鼓起勇氣嘗試真正地學習它們。那種“神奇”的品質,那種排他性的感覺,將我擋在門外。

When I did finally start cobbling together my own little interpreters, I quickly learned that, of course, there is no magic at all. It’s just code, and the people who hack on languages are just people.

當我最終開始拼湊我自己的小解釋器時,我很快意識到,根本就沒有魔法。它只是代碼,而那些玩弄語言的人也只是普通人。

There are a few techniques you don’t often encounter outside of languages, and some parts are a little difficult. But not more difficult than other obstacles you’ve overcome. My hope is that if you’ve felt intimidated by languages, and this book helps you overcome that fear, maybe I’ll leave you just a tiny bit braver than you were before.

有一些技巧您在語言之外不會經常遇到,而且有些部分有點難。但不會比您克服的其他障礙更困難。我希望,如果您對語言感到害怕,而這本書能幫助您克服這種恐懼,也許我會讓您比以前更勇敢一點。

And, who knows, maybe you will make the next great language. Someone has to.

而且,說不準,你也許會創造出下一個偉大的語言,畢竟總要有人做。

1 . 2 How the Book is Organized

1.2 本書的組織方式

This book is broken into three parts. You’re reading the first one now. It’s a couple of chapters to get you oriented, teach you some of the lingo that language hackers use, and introduce you to Lox, the language we’ll be implementing.

這本書分為三個部分。您現在正在讀的是第一部分。這部分用了幾章來讓您進入狀態,教您一些語言黑客使用的行話,並向您介紹我們將要實現的語言Lox。

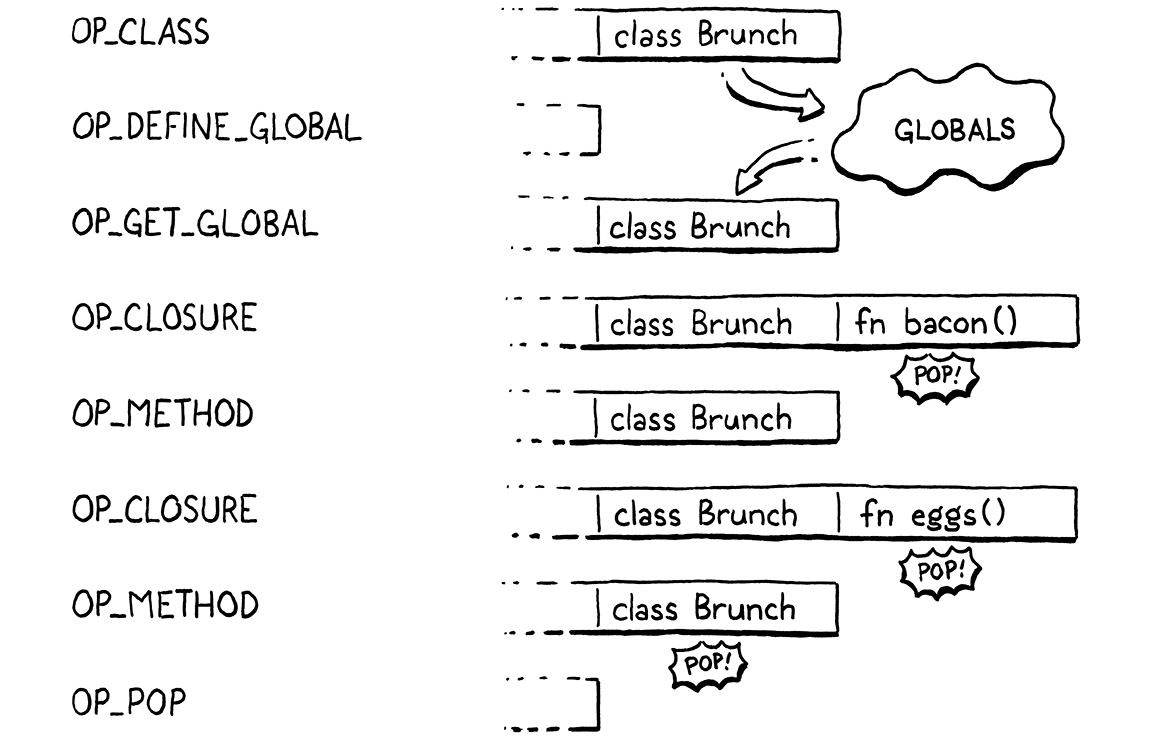

Each of the other two parts builds one complete Lox interpreter. Within those parts, each chapter is structured the same way. The chapter takes a single language feature, teaches you the concepts behind it, and walks through an implementation.

其他兩個部分則分別構建一個完整的Lox解釋器。在這些部分中,每個章節的結構都是相同的。 每一章節挑選一個語言功能點,教您背後對應的概念,並逐步介紹實現方法。

It took a good bit of trial and error on my part, but I managed to carve up the two interpreters into chapter-sized chunks that build on the previous chapters but require nothing from later ones. From the very first chapter, you’ll have a working program you can run and play with. With each passing chapter, it grows increasingly full-featured until you eventually have a complete language.

我花了不少時間去試錯,但我還是成功地把這兩個解釋器按照章節分成了一些小塊,每一小塊的內容都會建立在前面幾章的基礎上,但不需要後續章節的知識。從第一章開始,你就會有一個可以運行和使用的工作程序。隨著章節的推移,它的功能越來越豐富,直到你最終擁有一門完整的語言。

Aside from copious, scintillating English prose, chapters have a few other delightful facets:

除了大量妙趣橫生的英文段落,章節中還會包含一些其它的驚喜:

1.2.1 The code

1.2.1 代碼

We’re about crafting interpreters, so this book contains real code. Every single line of code needed is included, and each snippet tells you where to insert it in your ever-growing implementation.

本書是關於製作解釋器的,所以其中會包含真正的代碼。所需要的每一行代碼都需要包含在內,而且每個代碼片段都會告知您需要插入到實現代碼中的什麼位置。

Many other language books and language implementations use tools like Lex and Yacc, so-called compiler-compilers that automatically generate some of the source files for an implementation from some higher level description. There are pros and cons to tools like those, and strong opinions—some might say religious convictions—on both sides.

許多其他的語言書籍和語言實現都使用Lex和Yacc3這樣的工具,也就是所謂的編譯器-編譯器,可以從一些更高層次的(語法)描述中自動生成一些實現的源文件。這些工具有利有弊,而且雙方都有強烈的主張--有些人可能將其說成是信仰。

We will abstain from using them here. I want to ensure there are no dark corners where magic and confusion can hide, so we’ll write everything by hand. As you’ll see, it’s not as bad as it sounds and it means you really will understand each line of code and how both interpreters work.

我們這裡不會使用這些工具。我想確保魔法和困惑不會藏在黑暗的角落,所以我們會選擇手寫所有代碼。正如您將看到的,這並沒有聽起來那麼糟糕,因為這意味著您將真正理解每一行代碼以及兩種解釋器的工作方式。

A book has different constraints from the “real world” and so the coding style here might not always reflect the best way to write maintainable production software. If I seem a little cavalier about, say, omitting

privateor declaring a global variable, understand I do so to keep the code easier on your eyes. The pages here aren’t as wide as your IDE and every character counts.

為了寫書,書中代碼和“真實世界”的代碼是有區別的,因此這裡的代碼風格可能並不是編寫可維護的生產型軟件的最佳方式。可能我的某些寫法是不太準確的,比如省略private或者聲明全局變量,請理解我這樣做是為了讓您更容易看懂代碼。書頁不像IDE窗口那麼寬,所以每一個字符都很珍貴。

Also, the code doesn’t have many comments. That’s because each handful of lines is surrounded by several paragraphs of honest-to-God prose explaining it. When you write a book to accompany your program, you are welcome to omit comments too. Otherwise, you should probably use

//a little more than I do.

另外,代碼也不會有太多的註釋。這是因為每一部分代碼前後,都使用了一些真的很簡潔的文字來對其進行解釋。當你寫一本書來配合你的程序時,歡迎你也省略註釋。否則,你可能應該比我使用更多的 //。

While the book contains every line of code and teaches what each means, it does not describe the machinery needed to compile and run the interpreter. I assume you can slap together a makefile or a project in your IDE of choice in order to get the code to run. Those kinds of instructions get out of date quickly, and I want this book to age like XO brandy, not backyard hooch.

雖然這本書包含了每一行代碼,並教授了每一行代碼的含義,但它沒有描述編譯和運行解釋器所需的機制。我假設你可以簡單地拼湊出一個makefile,或者創建一個心儀的IDE中的一個工程,來讓代碼運行起來。 那種類型的說明很快就會過時,我希望這本書能像XO白蘭地一樣醇久,而不是像家釀酒(一樣易過期)。

1.2.2 Snippets

1.2.2 片段

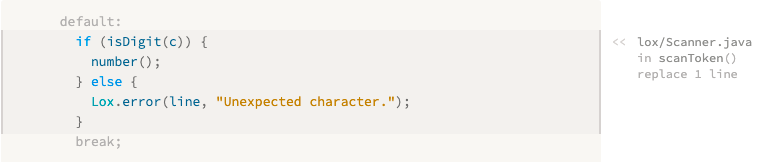

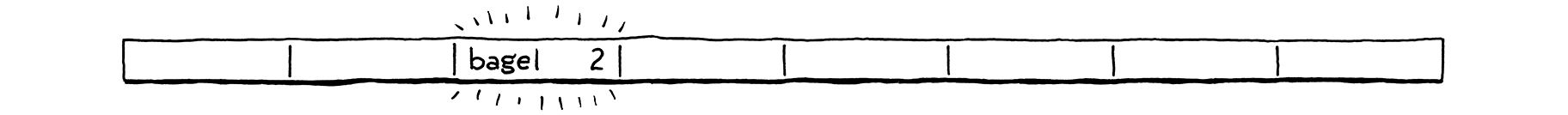

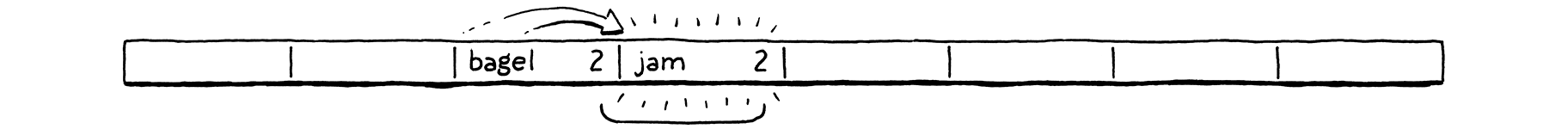

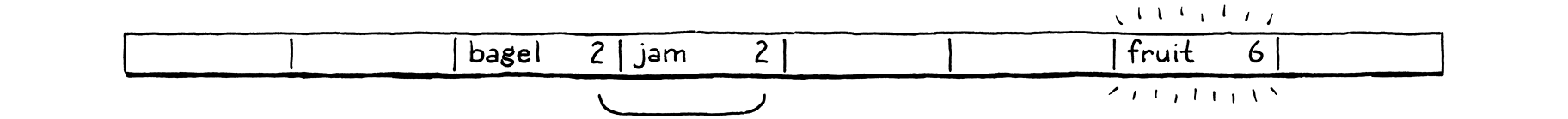

Since the book contains literally every line of code needed for the implementations, the snippets are quite precise. Also, because I try to keep the program in a runnable state even when major features are missing, sometimes we add temporary code that gets replaced in later snippets.

因為這本書包含了實現所需的每一行代碼,所以代碼片段相當精確。此外,即使是在缺少主要功能的時候,我也嘗試將程序保持在可運行狀態。因此我們有時會添加臨時代碼,這些代碼將在後面被其他的代碼片段替換。

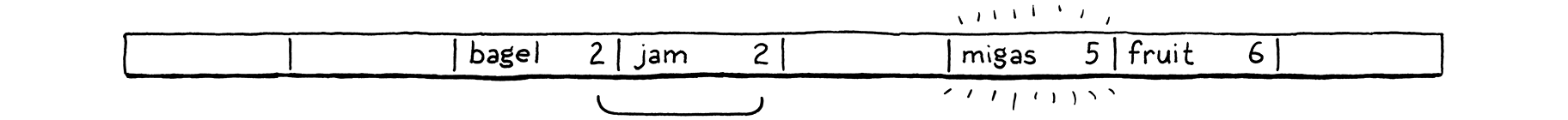

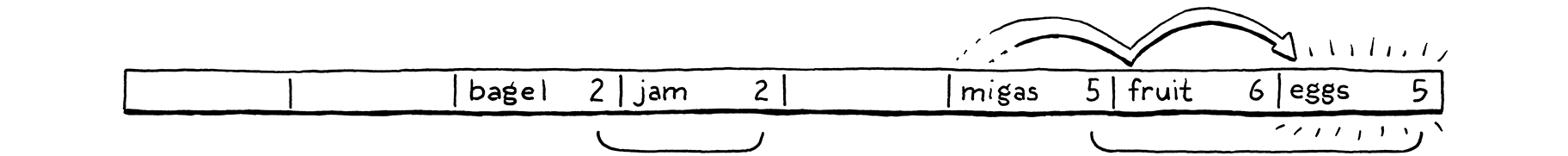

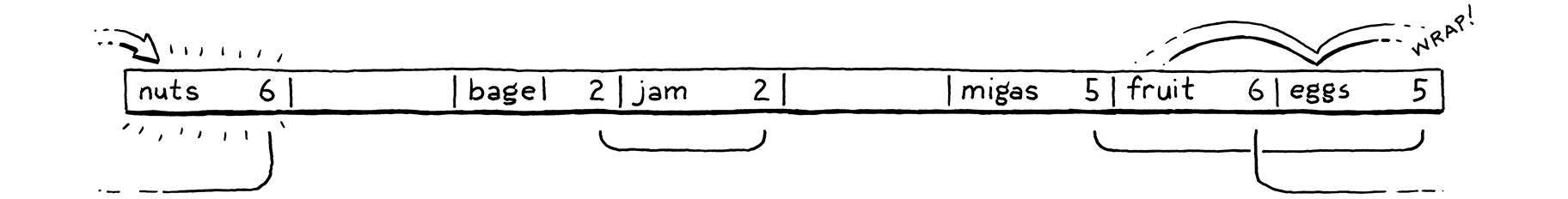

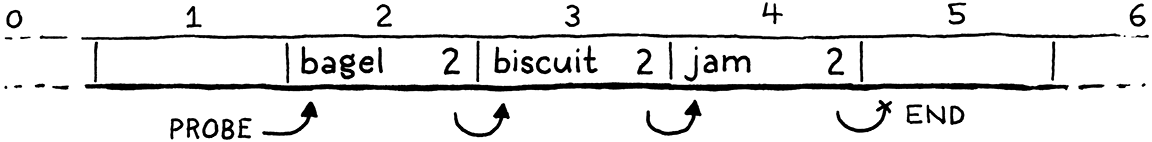

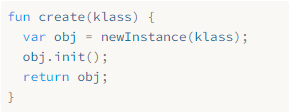

A snippet with all the bells and whistles looks like this:

一個完整的代碼片段可能如下所示:

In the center, you have the new code to add. It may have a few faded out lines above or below to show where it goes in the existing surrounding code. There is also a little blurb telling you in which file and where to place the snippet. If that blurb says “replace _ lines”, there is some existing code between the faded lines that you need to remove and replace with the new snippet.

中間是要添加的新代碼。這部分代碼的上面或下面可能有一些淡出的行,以顯示它在周圍代碼中的位置。還會附有一小段介紹,告訴您在哪個文件中以及在哪裡放置代碼片段。如果簡介說要“replace _ lines”,表明在淺色的行之間有一些現有的代碼需要刪除,並替換為新的代碼片段。

1.2.3 Asides

1.2.3 題外話

Asides contain biographical sketches, historical background, references to related topics, and suggestions of other areas to explore. There’s nothing that you need to know in them to understand later parts of the book, so you can skip them if you want. I won’t judge you, but I might be a little sad.

題外話中包含傳記簡介、歷史背景、對相關主題的引用以及對其他要探索的領域的建議。 您無需深入瞭解就可以理解本書的後續部分,因此可以根據需要跳過它們。 我不會批評你,但我可能會有些難過。【注:由於排版原因,在翻譯的時候,將有用的旁白信息作為腳註附在章節之後】

1.2.4 Challenge

1.2.4 挑戰

Each chapter ends with a few exercises. Unlike textbook problem sets which tend to review material you already covered, these are to help you learn more than what’s in the chapter. They force you to step off the guided path and explore on your own. They will make you research other languages, figure out how to implement features, or otherwise get you out of your comfort zone.

每章結尾都會有一些練習題。 不像教科書中的習題集那樣用於回顧已講述的內容,這些習題是為了幫助您學習更多的知識,而不僅僅是本章中的內容。 它們會迫使您走出文章指出的路線,自行探索。 它們將要求您研究其他語言,弄清楚如何實現功能,換句話說,就是使您走出舒適區。

Vanquish the challenges and you’ll come away with a broader understanding and possibly a few bumps and scrapes. Or skip them if you want to stay inside the comfy confines of the tour bus. It’s your book.

克服挑戰,您將獲得更廣泛的理解,也可能遇到一些挫折。 如果您想留在旅遊巴士的舒適區內,也可以跳過它們。 都隨你便4。

1.2.5 Design notes

1.2.5 設計筆記

Most “programming language” books are strictly programming language implementation books. They rarely discuss how one might happen to design the language being implemented. Implementation is fun because it is so precisely defined. We programmers seem to have an affinity for things that are black and white, ones and zeroes.

大多數編程語言書籍都是嚴格意義上的編程語言實現書籍。他們很少討論如何設計正在實現的語言。實現之所以有趣,是因為它的定義是很精確的。我們程序員似乎很喜歡黑白、1和0這樣的事物5。

Personally, I think the world only needs so many implementations of FORTRAN 77. At some point, you find yourself designing a new language. Once you start playing that game, then the softer, human side of the equation becomes paramount. Things like what features are easy to learn, how to balance innovation and familiarity, what syntax is more readable and to whom.

就個人而言,我認為世界只需要這麼多的FORTRAN 77實現。在某個時候,您會發現自己正在設計一種新的語言。 一旦開始這樣做,方程式中較柔和,人性化的一面就變得至關重要。 諸如哪些功能易於學習,如何在創新和熟悉度之間取得平衡,哪種語法更易讀以及對誰有幫助6。

All of that stuff profoundly affects the success of your new language. I want your language to succeed, so in some chapters I end with a “design note”, a little essay on some corner of the human aspect of programming languages. I’m no expert on this—I don’t know if anyone really is—so take these with a large pinch of salt. That should make them tastier food for thought, which is my main aim.

所有這些都會對您的新語言的成功產生深遠的影響。 我希望您的語言取得成功,因此在某些章節中,我以一篇“設計筆記”結尾,這些是關於編程語言的人文方面的一些文章。我並不是這方面的專家——我不確定是否有人真的精通這些,因此,請您在閱讀這些文字的時候仔細評估。這樣的話,這些文字就能成為您思考的食材,這也正是我的目標。

1 . 3 The First Interpreter

1.3 第一個解釋器

We’ll write our first interpreter, jlox, in Java. The focus is on concepts. We’ll write the simplest, cleanest code we can to correctly implement the semantics of the language. This will get us comfortable with the basic techniques and also hone our understanding of exactly how the language is supposed to behave.

我們將用Java編寫第一個解釋器jlox。(這裡的)主要關注點是概念。 我們將編寫最簡單,最乾淨的代碼,以正確實現該語言的語義。 這樣能夠幫助我們熟悉基本技術,並磨練對語言表現形式的確切理解。

Java is a great language for this. It’s high level enough that we don’t get overwhelmed by fiddly implementation details, but it’s still pretty explicit. Unlike scripting languages, there tends to be less complex machinery hiding under the hood, and you’ve got static types to see what data structures you’re working with.

Java是一門很適合這種場景的語言。它的級別足夠高,我們不會被繁瑣的實現細節淹沒,但代碼仍是非常明確的。與腳本語言不同的是,它的底層沒有隱藏太過複雜的機制,你可以使用靜態類型來查看正在處理的數據結構。

I also chose Java specifically because it is an object-oriented language. That paradigm swept the programming world in the 90s and is now the dominant way of thinking for millions of programmers. Odds are good you’re already used to organizing code into classes and methods, so we’ll keep you in that comfort zone.

我選擇Java還有特別的原因,就是因為它是一種面向對象的語言。 這種範式在90年代席捲了整個編程世界,如今已成為數百萬程序員的主流思維方式。 很有可能您已經習慣了將代碼組織到類和方法中,因此我們將讓您在舒適的環境中學習。

While academic language folks sometimes look down on object-oriented languages, the reality is that they are widely used even for language work. GCC and LLVM are written in C++, as are most JavaScript virtual machines. Object-oriented languages are ubiquitous and the tools and compilers for a language are often written in the same language.

雖然學術語言專家有時瞧不起面嚮對象語言,但事實上,它們即使在語言工作中也被廣泛使用。GCC和LLVM是用C++編寫的,大多數JavaScript虛擬機也是這樣。 面向對象的語言無處不在,並且針對該語言的工具和編譯器通常是用同一種語言編寫的7。

And, finally, Java is hugely popular. That means there’s a good chance you already know it, so there’s less for you to learn to get going in the book. If you aren’t that familiar with Java, don’t freak out. I try to stick to a fairly minimal subset of it. I use the diamond operator from Java 7 to make things a little more terse, but that’s about it as far as “advanced” features go. If you know another object-oriented language like C# or C++, you can muddle through.

最後,Java非常流行。 這意味著您很有可能已經瞭解它了,所以你要學習的東西就更少了。 如果您不太熟悉Java,也請不要擔心。 我儘量只使用它的最小子集。我使用Java 7中的菱形運算符使代碼看起來更簡潔,但就“高級”功能而言,僅此而已。 如果您瞭解其它面向對象的語言(例如C#或C++),就沒有問題。

By the end of part II, we’ll have a simple, readable implementation. What we won’t have is a fast one. It also takes advantage of the Java virtual machine’s own runtime facilities. We want to learn how Java itself implements those things.

在第二部分結束時,我們將得到一個簡單易讀的實現。 但是我們得到的不會是一個執行效率高的解釋器。它還是利用了Java虛擬機自身的運行時工具。我們想要學習Java本身是如何實現這些東西的。

1 . 4 The Second Interpreter

1.4 第二個解釋器

So in the next part, we start all over again, but this time in C. C is the perfect language for understanding how an implementation really works, all the way down to the bytes in memory and the code flowing through the CPU.

所以在下一部分,我們將從頭開始,但這一次是用C語言。C語言是理解實現編譯器工作方式的完美語言,一直到內存中的字節和流經CPU的代碼。

A big reason that we’re using C is so I can show you things C is particularly good at, but that does mean you’ll need to be pretty comfortable with it. You don’t have to be the reincarnation of Dennis Ritchie, but you shouldn’t be spooked by pointers either.

我們使用C語言的一個重要原因是,我可以向您展示C語言特別擅長的東西,但這並不意味著您需要非常熟練地使用它。您不必是丹尼斯·裡奇(Dennis Ritchie)的轉世,但也不應被指針嚇倒。

If you aren’t there yet, pick up an introductory book on C and chew through it, then come back here when you’re done. In return, you’ll come away from this book an even stronger C programmer. That’s useful given how many language implementations are written in C: Lua, CPython, and Ruby’s MRI, to name a few.

如果你(對C的掌握)還沒到那一步,找一本關於C的入門書,仔細閱讀,讀完後再回來。作為回報,從這本書中你將成為一個更優秀的C程序員。可以想想有多少語言實現是用C完成的: Lua、CPython和Ruby 的 MRI等,這裡僅舉幾例。

In our C interpreter, clox, we are forced to implement for ourselves all the things Java gave us for free. We’ll write our own dynamic array and hash table. We’ll decide how objects are represented in memory, and build a garbage collector to reclaim it.

在我們的C解釋器clox中8,我們不得不自己實現那些Java免費提供給我們的東西。 我們將編寫自己的動態數組和哈希表。 我們將決定對象在內存中的表示方式,並構建一個垃圾回收器來回收它。

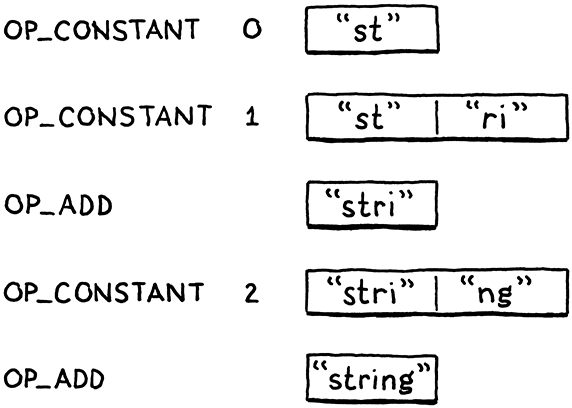

Our Java implementation was focused on being correct. Now that we have that down, we’ll turn to also being fast. Our C interpreter will contain a compiler that translates Lox to an efficient bytecode representation (don’t worry, I’ll get into what that means soon) which it then executes. This is the same technique used by implementations of Lua, Python, Ruby, PHP, and many other successful languages.

我們的Java版實現專注於正確性。 既然我們已經完成了,那麼我們就要變快。 我們的C解釋器將包含一個編譯器9,該編譯器會將Lox轉換為有效的字節碼形式(不用擔心,我很快就會講解這是什麼意思)之後它會執行對應的字節碼。 這與Lua,Python,Ruby,PHP和許多其它成功語言的實現所使用的技術相同。

We’ll even try our hand at benchmarking and optimization. By the end, we’ll have a robust, accurate, fast interpreter for our language, able to keep up with other professional caliber implementations out there. Not bad for one book and a few thousand lines of code.

我們甚至會嘗試進行基準測試和優化。 到最後,我們將為lox語言提供一個強大,準確,快速的解釋器,並能夠不落後於其他專業水平的實現。對於一本書和幾千行代碼來說已經不錯了。

CHALLENGES

習題

1、There are at least six domain-specific languages used in the little system I cobbled together to write and publish this book. What are they?

在我編寫的這個小系統中,至少有六種特定領域語言(DSL),它們是什麼?

2、Get a “Hello, world!” program written and running in Java. Set up whatever Makefiles or IDE projects you need to get it working. If you have a debugger, get comfortable with it and step through your program as it runs.

使用Java編寫並運行一個“Hello, world!”程序,配置一個你需要的makefile或IDE項目讓它跑起來。如果您有調試器,請先熟悉一下,並在程序運行時對代碼逐步調試。

3、Do the same thing for C. To get some practice with pointers, define a doubly-linked list of heap-allocated strings. Write functions to insert, find, and delete items from it. Test them.

對C也進行同樣的操作。為了練習使用指針,可以定義一個堆分配字符串的雙向鏈表。編寫函數以插入,查找和刪除其中的項目。 測試編寫的函數。

DESIGN NOTE: WHAT’S IN A NAME?

設計筆記:名稱是什麼?

One of the hardest challenges in writing this book was coming up with a name for the language it implements. I went through pages of candidates before I found one that worked. As you’ll discover on the first day you start building your own language, naming is deviously hard. A good name satisfies a few criteria:

- It isn’t in use. You can run into all sorts of trouble, legal and social, if you inadvertently step on someone else’s name.

- It’s easy to pronounce. If things go well, hordes of people will be saying and writing your language’s name. Anything longer than a couple of syllables or a handful of letters will annoy them to no end.

- It’s distinct enough to search for. People will Google your language’s name to learn about it, so you want a word that’s rare enough that most results point to your docs. Though, with the amount of AI search engines are packing today, that’s less of an issue. Still, you won’t be doing your users any favors if you name your language “for”.

- It doesn’t have negative connotations across a number of cultures. This is hard to guard for, but it’s worth considering. The designer of Nimrod ended up renaming his language to “Nim” because too many people only remember that Bugs Bunny used “Nimrod” (ironically, actually) as an insult.

If your potential name makes it through that gauntlet, keep it. Don’t get hung up on trying to find an appellation that captures the quintessence of your language. If the names of the world’s other successful languages teach us anything, it’s that the name doesn’t matter much. All you need is a reasonably unique token.

寫這本書最困難的挑戰之一是為它所實現的語言取個名字。我翻了好幾頁的備選名才找到一個合適的。當你某一天開始構建自己的語言時,你就會發現命名是非常困難的。一個好名字要滿足幾個標準:

- 尚未使用。如果您不小心使用了別人的名字,就可能會遇到各種法律和社會上的麻煩。

- 容易發音。如果一切順利,將會有很多人會說和寫您的語言名稱。 超過幾個音節或幾個字母的任何內容都會使他們陷入無休止的煩惱。

- 足夠獨特,易於搜索。人們會Google你的語言的名字來瞭解它,所以你需要一個足夠獨特的單詞,以便大多數搜索結果都會指向你的文檔。不過,隨著人工智能搜索引擎數量的增加,這已經不是什麼大問題了。但是,如果您將語言命名為“ for”,那對用戶基本不會有任何幫助。

- 在多種文化中,都沒有負面的含義。這很難防範,但是值得深思。Nimrod的設計師最終將其語言重命名為“ Nim”,因為太多的人只記得Bugs Bunny使用“ Nimrod”作為一種侮辱(其實是諷刺)。

如果你潛在的名字通過了考驗,就保留它吧。不要糾結於尋找一個能夠抓住你語言精髓的名稱。如果說世界上其他成功的語言的名字教會了我們什麼的話,那就是名字並不重要。您所需要的只是一個相當獨特的標記。

-

靜態類型系統尤其需要嚴格的形式推理。破解類型系統就像證明數學定理一樣。事實證明這並非巧合。 上世紀初,Haskell Curry和William Alvin Howard證明瞭它們是同一枚硬幣的兩個方面:Curry-Howard同構。 ↩

-

pidgins,洋涇浜語言,一種混雜的英語 ↩

-

Yacc是一個工具,它接收語法文件並生成編譯器的源文件,因此它有點像一個輸出“編譯器”的編譯器,在術語中叫作“compiler-compiler”,即編譯器的編譯器。Yacc並不是同類工具中的第一個,這就是為什麼它被命名為“Yacc”—Yet Another Compiler-Compiler(另一個Compiler-Compiler)。後來還有一個類似的工具是Bison,它的名字源於Yacc和yak的發音,是一個雙關語。 ↩

-

警告:挑戰題目通常要求您對正在構建的解釋器進行更改。您需要在代碼副本中實現這些功能。後面的章節都假設你的解釋器處於原始(未解決挑戰題)狀態。 ↩

-

我知道很多語言黑客的職業就基於此。您將一份語言規範塞到他們的門下,等上幾個月,代碼和基準測試結果就出來了。 ↩

-

希望您的新語言不會將對打孔卡寬度的假設硬編碼到語法中。 ↩

-

編譯器以一種語言讀取文件。 翻譯它們,並以另一種語言輸出文件。 您可以使用任何一種語言(包括與目標語言相同的語言)來實現編譯器,該過程稱為“自舉”。你現在還不能使用編譯器本身來編譯你自己的編譯器,但是如果你用其它語言為你的語言寫了一個編譯器,你就可以用那個編譯器編譯一次你的編譯器。現在,您可以使用自己的編譯器的已編譯版本來編譯自身的未來版本,並且可以從另一個編譯器中丟棄最初的已編譯版本。 這就是所謂的“自舉”,通過自己的引導程序將自己拉起來。 ↩

-

我把這個名字讀作“sea-locks”,但是你也可以讀作“clocks”,如果你願意的話可以像希臘人讀“x”那樣將其讀作“clochs”, ↩

-

你以為這只是一本講解釋器的書嗎?它也是一本講編譯器的書。買一送一。 ↩

2.領土地圖 A Map of the Territory

You must have a map, no matter how rough. Otherwise you wander all over the place. In “The Lord of the Rings” I never made anyone go farther than he could on a given day.

——J.R.R. Tolkien

你必須要有一張地圖,無論它是多麼粗糙。否則你就會到處亂逛。在《指環王》中,我從未讓任何人在某一天走得超出他力所能及的範圍。

We don’t want to wander all over the place, so before we set off, let’s scan the territory charted by previous language implementers. It will help us understand where we are going and alternate routes others take.

我們不想到處亂逛,所以在我們開始之前,讓我們先瀏覽一下以前的語言實現者所繪製的領土。它能幫助我們瞭解我們的目的地和其他人採用的備選路線。

First, let me establish a shorthand. Much of this book is about a language’s implementation, which is distinct from the language itself in some sort of Platonic ideal form. Things like “stack”, “bytecode”, and “recursive descent”, are nuts and bolts one particular implementation might use. From the user’s perspective, as long as the resulting contraption faithfully follows the language’s specification, it’s all implementation detail.

首先,我先做個簡單說明。本書的大部分內容都是關於語言的實現,它與語言本身這種柏拉圖式的理想形式有所不同。諸如“堆疊”,“位元組碼”和“遞迴下降”之類的東西是某個特定實現中可能使用的基本要素。從使用者的角度來說,只要最終產生的裝置能夠忠實地遵循語言規範,這些都是東西不過是他們不關心的實現細節罷了。

We’re going to spend a lot of time on those details, so if I have to write “language implementation” every single time I mention them, I’ll wear my fingers off. Instead, I’ll use “language” to refer to either a language or an implementation of it, or both, unless the distinction matters.

我們將會花很多時間在這些細節上,所以如果我每次提及的時候都寫“語言實現”,我的手指都會被磨掉。相反,除非有重要的區別,否則我將使用“語言”來指代一種語言或該語言的一種實現,或兩者皆有。

2 . 1 The Parts of a Language

2.1 語言的各部分

Engineers have been building programming languages since the Dark Ages of computing. As soon as we could talk to computers, we discovered doing so was too hard, and we enlisted their help. I find it fascinating that even though today’s machines are literally a million times faster and have orders of magnitude more storage, the way we build programming languages is virtually unchanged.

自計算機的黑暗時代以來,工程師們就一直在構建程式語言。當我們可以和計算機對話的時候,我們發現這樣做太難了,於是我們尋求電腦的幫助。我覺得很有趣的是,即使今天的機器確實快了一百萬倍,儲存空間也大了幾個數量級,但我們構建程式語言的方式幾乎沒有改變。

Though the area explored by language designers is vast, the trails they’ve carved through it are few. Not every language takes the exact same path—some take a shortcut or two—but otherwise they are reassuringly similar from Rear Admiral Grace Hopper’s first COBOL compiler all the way to some hot new transpile-to-JavaScript language whose “documentation” consists entirely of a single poorly-edited README in a Git repository somewhere.

儘管語言設計師所探索的領域遼闊,但他們往往都走到相似的幾條路上。 並非每種語言都採用完全相同的路徑(有些會採用一種或兩種捷徑),但除此之外,從海軍少將Grace Hopper的第一個COBOL編譯器,一直到一些熱門的可以轉譯到JavaScript的語言(JS的 "文件 "甚至完全是由Git倉庫中一個編輯得很差的README組成的1),都呈現出相似的特徵,這令人十分欣慰。

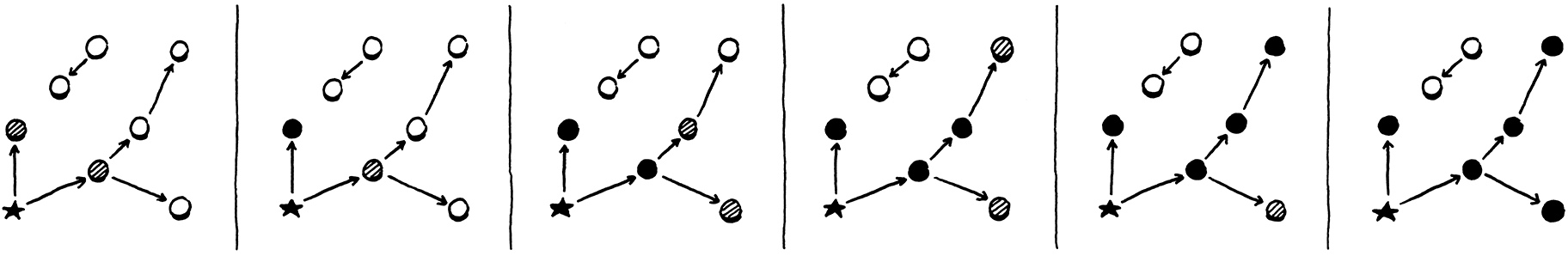

I visualize the network of paths an implementation may choose as climbing a mountain. You start off at the bottom with the program as raw source text, literally just a string of characters. Each phase analyzes the program and transforms it to some higher-level representation where the semantics—what the author wants the computer to do—becomes more apparent.

我把一個語言實現可能選擇的路徑網路類比為爬山。你從最底層開始,程式是原始的源文字,實際上只是一串字元。每個階段都會對程式進行分析,並將其轉換為更高層次的表現形式,從而使語義(作者希望計算機做什麼)變得更加明顯。

Eventually we reach the peak. We have a bird’s-eye view of the users’s program and can see what their code means. We begin our descent down the other side of the mountain. We transform this highest-level representation down to successively lower-level forms to get closer and closer to something we know how to make the CPU actually execute.

最終我們達到了峰頂。我們可以鳥瞰使用者的程式,可以看到他們的程式碼含義是什麼。我們開始從山的另一邊下山。我們將這個最高階的表示形式轉化為連續的較低階別的形式,從而越來越接近我們所知道的如何讓CPU真正執行的形式。

Let’s trace through each of those trails and points of interest. Our journey begins on the left with the bare text of the user’s source code:

讓我們追隨著這一條條路徑和點前進吧。我們的旅程從左邊的使用者原始碼的純文字開始:

2.1.1 Scanning

2.1.1 掃描

The first step is scanning, also known as lexing, or (if you’re trying to impress someone) lexical analysis. They all mean pretty much the same thing. I like “lexing” because it sounds like something an evil supervillain would do, but I’ll use “scanning” because it seems to be marginally more commonplace.

第一步是掃描,也就是所謂的詞法分析 ( lexing 或者強調寫法 lexical analysis )。掃描和詞法分析的意思相近。我喜歡詞法分析這個描述,因為這聽起來像是一個邪惡的超級大壞蛋會做的事情,但我還是用掃描,因為它似乎更常見一些。

A scanner (or lexer) takes in the linear stream of characters and chunks them together into a series of something more akin to “words”. In programming languages, each of these words is called a token. Some tokens are single characters, like

(and,. Others may be several characters long, like numbers (123), string literals ("hi!"), and identifiers (min).

掃描器(或詞法解析器)接收線性字元流,並將它們切分成一系列更類似於“單詞”的東西。在程式語言中,這些詞的每一個都被稱為詞法單元。有些詞法單元是單個字元,比如(和 ,。其他的可能是幾個字元長的,比如數字(123)、字串字元("hi!")和識別符號(min)。

Some characters in a source file don’t actually mean anything. Whitespace is often insignificant and comments, by definition, are ignored by the language. The scanner usually discards these, leaving a clean sequence of meaningful tokens.

原始檔中的一些字元實際上沒有任何意義。空格通常是無關緊要的,而註釋,從定義就能看出來,會被變成語言忽略。掃描器通常會丟棄這些字元,留下一個乾淨的有意義的詞法單元序列。

![[var] [average] [=] [(] [min] [+] [max] [)] [/] [2] [;]](2.%E9%A0%98%E5%9C%9F%E5%9C%B0%E5%9C%96/tokens.png)

2.1.2 Parsing

2.1.2 語法分析

The next step is parsing. This is where our syntax gets a grammar—the ability to compose larger expressions and statements out of smaller parts. Did you ever diagram sentences in English class? If so, you’ve done what a parser does, except that English has thousands and thousands of “keywords” and an overflowing cornucopia of ambiguity. Programming languages are much simpler.

下一步是解析。 這就是我們從句法中得到語法的地方——語法能夠將較小的部分組成較大的表示式和語句。你在英語課上做過語法圖解嗎?如果有,你就做了解析器所做的事情,區別在於,英語中有成千上萬的“關鍵字”和大量的歧義,而程式語言要簡單得多。

A parser takes the flat sequence of tokens and builds a tree structure that mirrors the nested nature of the grammar. These trees have a couple of different names—“parse tree” or “abstract syntax tree”—depending on how close to the bare syntactic structure of the source language they are. In practice, language hackers usually call them “syntax trees”, “ASTs”, or often just “trees”.

解析器將扁平的詞法單元序列轉化為樹形結構,樹形結構能更好地反映語法的巢狀本質。這些樹有兩個不同的名稱:解析樹或抽象語法樹,這取決於它們與源語言的語法結構有多接近。在實踐中,語言駭客通常稱它們為“語法樹”、“AST”,或者乾脆直接說“樹”。

Parsing has a long, rich history in computer science that is closely tied to the artificial intelligence community. Many of the techniques used today to parse programming languages were originally conceived to parse human languages by AI researchers who were trying to get computers to talk to us.

解析在電腦科學中有著悠久而豐富的歷史,它與人工智慧界有著密切的聯絡。今天用於解析程式語言的許多技術最初被人工智慧研究人員用於解析人類語言,人工智慧研究人員試圖透過這些技術讓計算機能與我們對話。

It turns out human languages are too messy for the rigid grammars those parsers could handle, but they were a perfect fit for the simpler artificial grammars of programming languages. Alas, we flawed humans still manage to use those simple grammars incorrectly, so the parser’s job also includes letting us know when we do by reporting syntax errors.

事實證明,人類語言對於只能處理僵化語法的解析器來說太混亂了,但面對程式語言這種簡單的人造語法時,解析器表現得十分合適。唉,可惜我們這些有缺陷的人類在使用這些簡單的語法時,仍然會不停地出錯,因此解析器的工作還包括透過報告語法錯誤讓我們知道出錯了。

2 . 1 . 3 Static analysis

2.1.3 靜態分析

The first two stages are pretty similar across all implementations. Now, the individual characteristics of each language start coming into play. At this point, we know the syntactic structure of the code—things like which expressions are nested in which others—but we don’t know much more than that.

在所有實現中,前兩個階段都非常相似。 現在,每種語言的個性化特徵開始發揮作用。 至此,我們知道了程式碼的語法結構(諸如哪些表示式巢狀在其他表示式中)之類的東西,但是我們知道的也就僅限於此了。

In an expression like

a + b, we know we are addingaandb, but we don’t know what those names refer to. Are they local variables? Global? Where are they defined?

在a + b這樣的表示式中,我們知道我們要把a和b相加,但我們不知道這些名字指的是什麼。它們是區域性變數嗎?全域性變數?它們在哪裡被定義?

The first bit of analysis that most languages do is called binding or resolution. For each identifier we find out where that name is defined and wire the two together. This is where scope comes into play—the region of source code where a certain name can be used to refer to a certain declaration.

大多數語言所做的第一點分析叫做繫結或決議。對於每一個識別符號,我們都要找出定義該名稱的地方,並將兩者連線起來。這就是作用域的作用——在這個原始碼區域中,某個名字可以用來引用某個宣告。

If the language is statically typed, this is when we type check. Once we know where

aandbare declared, we can also figure out their types. Then if those types don’t support being added to each other, we report a type error.

如果語言是靜態型別的,這就是我們進行型別檢查的時機。一旦我們知道了a和b的宣告位置,我們也可以弄清楚它們的型別。然後如果這些型別不支援相加,我們就會報告一個型別錯誤2。

Take a deep breath. We have attained the summit of the mountain and a sweeping view of the user’s program. All this semantic insight that is visible to us from analysis needs to be stored somewhere. There are a few places we can squirrel it away:

- Often, it gets stored right back as attributes on the syntax tree itself—extra fields in the nodes that aren’t initialized during parsing but get filled in later.

- Other times, we may store data in a look-up table off to the side. Typically, the keys to this table are identifiers—names of variables and declarations. In that case, we call it a symbol table and the values it associates with each key tell us what that identifier refers to.

- The most powerful bookkeeping tool is to transform the tree into an entirely new data structure that more directly expresses the semantics of the code. That’s the next section.

深吸一口氣。 我們已經到達了山頂,並對使用者的程式有了全面的瞭解。從分析中可見的所有語義資訊都需要儲存在某個地方。我們可以把它儲存在幾個地方:

- 通常,它會被直接儲存在語法樹本身的屬性中——屬性是節點中的額外欄位,這些欄位在解析時不會初始化,但在稍後會進行填充。

- 有時,我們可能會將資料儲存在外部的查詢表中。 通常,該表的關鍵字是識別符號,即變數和宣告的名稱。 在這種情況下,我們稱其為符號表,並且其中與每個鍵關聯的值告訴我們該識別符號所指的是什麼。

- 最強大的記錄工具是將樹轉化為一個全新的資料結構,更直接地表達程式碼的語義。這是下一節的內容。

Everything up to this point is considered the front end of the implementation. You might guess everything after this is the back end, but no. Back in the days of yore when “front end” and “back end” were coined, compilers were much simpler. Later researchers invented new phases to stuff between the two halves. Rather than discard the old terms, William Wulf and company lumped them into the charming but spatially paradoxical name middle end.

到目前為止,所有內容都被視為實現的前端。 你可能會猜至此以後是後端,其實並不是。 在過去的年代,當“前端”和“後端”被創造出來時,編譯器要簡單得多。 後來,研究人員在兩個半部之間引入了新階段。 威廉·沃爾夫(William Wulf)和他的同伴沒有放棄舊術語,而是新添加了一個迷人但有點自相矛盾的名稱“中端”。

2 . 1 . 4 Intermediate representations

2.1.4 中間碼

You can think of the compiler as a pipeline where each stage’s job is to organize the data representing the user’s code in a way that makes the next stage simpler to implement. The front end of the pipeline is specific to the source language the program is written in. The back end is concerned with the final architecture where the program will run.

你可以把編譯器看成是一條流水線,每個階段的工作是把代表使用者程式碼的資料組織起來,使下一階段的實現更加簡單。管道的前端是針對程式所使用的源語言編寫的。後端關注的是程式執行的最終架構。

In the middle, the code may be stored in some intermediate representation (or IR) that isn’t tightly tied to either the source or destination forms (hence “intermediate”). Instead, the IR acts as an interface between these two languages.

在中間階段,程式碼可能被儲存在一些中間程式碼(intermediate representation, 也叫IR)中,這些中間程式碼與原始檔或目的檔案形式都沒有緊密的聯絡(因此叫作 "中間")。相反,IR充當了這兩種語言之間的介面3。

This lets you support multiple source languages and target platforms with less effort. Say you want to implement Pascal, C and Fortran compilers and you want to target x86, ARM, and, I dunno, SPARC. Normally, that means you’re signing up to write nine full compilers: Pascal→x86, C→ARM, and every other combination.

這可以讓你更輕鬆地支援多種源語言和目標平臺。假設你想在x86、ARM、SPARC 平臺上實現Pascal、C和Fortran編譯器。通常情況下,這意味著你需要寫九個完整的編譯器:Pascal→x86,C→ARM,以及其他各種組合4。

A shared intermediate representation reduces that dramatically. You write one front end for each source language that produces the IR. Then one back end for each target architecture. Now you can mix and match those to get every combination.

一個共享的中間程式碼可以大大減少這種情況。你為每個產生IR的源語言寫一個前端。然後為每個目標平臺寫一個後端。現在,你可以將這些混搭起來,得到每一種組合。

There’s another big reason we might want to transform the code into a form that makes the semantics more apparent…

我們希望將程式碼轉化為某種語義更加明確的形式,還有一個重要的原因是。。。

2 . 1 . 5 Optimization

2.1.5 最佳化

Once we understand what the user’s program means, we are free to swap it out with a different program that has the same semantics but implements them more efficiently—we can optimize it.

一旦我們理解了使用者程式的含義,我們就可以自由地用另一個具有相同語義但實現效率更高的程式來交換它——我們可以對它進行最佳化。

A simple example is constant folding: if some expression always evaluates to the exact same value, we can do the evaluation at compile time and replace the code for the expression with its result. If the user typed in:

一個簡單的例子是常量摺疊:如果某個表示式求值得到的始終是完全相同的值,我們可以在編譯時進行求值,並用其結果替換該表示式的程式碼。 如果使用者輸入:

pennyArea = 3.14159 * (0.75 / 2) * (0.75 / 2);

We can do all of that arithmetic in the compiler and change the code to:

我們可以在編譯器中完成所有的算術運算,並將程式碼更改為:

pennyArea = 0.4417860938;

Optimization is a huge part of the programming language business. Many language hackers spend their entire careers here, squeezing every drop of performance they can out of their compilers to get their benchmarks a fraction of a percent faster. It can become a sort of obsession.

最佳化是程式語言業務的重要組成部分。許多語言駭客把他們的整個職業生涯都花在了這裡,竭盡所能地從他們的編譯器中擠出每一點效能,以使他們的基準測試速度提高百分之幾。有的時候這也會變成一種痴迷, 無法自拔。

We’re mostly going to hop over that rathole in this book. Many successful languages have surprisingly few compile-time optimizations. For example, Lua and CPython generate relatively unoptimized code, and focus most of their performance effort on the runtime.

我們在本書中通常會跳過這些棘手問題。令人驚訝的是許多成功的語言只有很少的編譯期最佳化。 例如,Lua和CPython生成沒怎麼最佳化過的程式碼,並將其大部分效能工作集中在執行時上5。

2 . 1 . 6 Code generation

2.1.6 程式碼生成

We have applied all of the optimizations we can think of to the user’s program. The last step is converting it to a form the machine can actually run. In other words generating code (or code gen), where “code” here usually refers to the kind of primitive assembly-like instructions a CPU runs and not the kind of “source code” a human might want to read.

我們已經將所有可以想到的最佳化應用到了使用者程式中。 最後一步是將其轉換為機器可以實際執行的形式。 換句話說,生成程式碼(或程式碼生成),這裡的“程式碼”通常是指CPU執行的類似於彙編的原始指令,而不是人類可能想要閱讀的“原始碼”。

Finally, we are in the back end, descending the other side of the mountain. From here on out, our representation of the code becomes more and more primitive, like evolution run in reverse, as we get closer to something our simple-minded machine can understand.

最後,我們到了後端,從山的另一側開始向下。 從現在開始,隨著我們越來越接近於思維簡單的機器可以理解的東西,我們對程式碼的表示變得越來越原始,就像逆向進化。

We have a decision to make. Do we generate instructions for a real CPU or a virtual one? If we generate real machine code, we get an executable that the OS can load directly onto the chip. Native code is lightning fast, but generating it is a lot of work. Today’s architectures have piles of instructions, complex pipelines, and enough historical baggage to fill a 747’s luggage bay.

我們需要做一個決定。 我們是為真實CPU還是虛擬CPU生成指令? 如果我們生成真實的機器程式碼,則會得到一個可執行檔案,作業系統可以將其直接載入到晶片上。 原生程式碼快如閃電,但生成它需要大量工作。 當今的體系結構包含大量指令,複雜的管線和足夠塞滿一架747行李艙的歷史包袱。

Speaking the chip’s language also means your compiler is tied to a specific architecture. If your compiler targets x86 machine code, it’s not going to run on an ARM device. All the way back in the 60s, during the Cambrian explosion of computer architectures, that lack of portability was a real obstacle.

使用晶片的語言也意味著你的編譯器是與特定的架構相繫結的。如果你的編譯器以x86機器程式碼為目標,那麼它就無法在ARM裝置上執行。追朔到上世紀60年代計算機體系結構 “寒武紀大爆發” 期間,這種缺乏可移植性的情況是一個真正的障礙6。

To get around that, hackers like Martin Richards and Niklaus Wirth, of BCPL and Pascal fame, respectively, made their compilers produce virtual machine code. Instead of instructions for some real chip, they produced code for a hypothetical, idealized machine. Wirth called this “p-code” for “portable”, but today, we generally call it bytecode because each instruction is often a single byte long.

為瞭解決這個問題,專家開始讓他們的編譯器生成虛擬機器程式碼,包括BCPL的設計者Martin Richards以及Pascal設計者Niklaus Wirth。他們不是為真正的晶片編寫指令,而是為一個假設的、理想化的機器編寫程式碼。Wirth稱這種p-code為“可移植程式碼”,但今天,我們通常稱它為位元組碼,因為每條指令通常都是一個位元組長。

These synthetic instructions are designed to map a little more closely to the language’s semantics, and not be so tied to the peculiarities of any one computer architecture and its accumulated historical cruft. You can think of it like a dense, binary encoding of the language’s low-level operations.

這些合成指令的設計是為了更緊密地對映到語言的語義上,而不必與任何一個計算機體系結構的特性和它積累的歷史錯誤繫結在一起。你可以把它想象成語言底層操作的密集二進位制編碼。

2 . 1 . 7 Virtual machine

2.1.7 虛擬機器

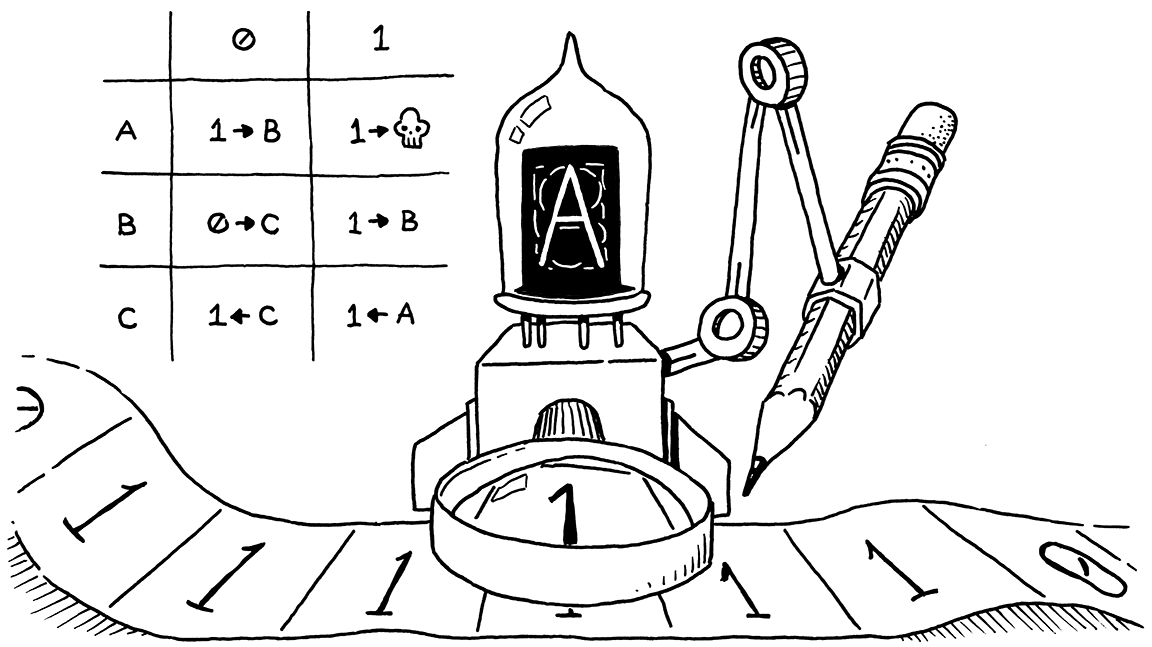

If your compiler produces bytecode, your work isn’t over once that’s done. Since there is no chip that speaks that bytecode, it’s your job to translate. Again, you have two options. You can write a little mini-compiler for each target architecture that converts the bytecode to native code for that machine. You still have to do work for each chip you support, but this last stage is pretty simple and you get to reuse the rest of the compiler pipeline across all of the machines you support. You’re basically using your bytecode as an intermediate representation.

如果你的編譯器產生了位元組碼,你的工作還沒有結束。因為沒有晶片可以解析這些位元組碼,因此你還需要進行翻譯。同樣,你有兩個選擇。你可以為每個目標體系結構編寫一個小型編譯器,將位元組碼轉換為該機器的本機程式碼7。你仍然需要針對你支援的每個晶片做一些工作,但最後這個階段非常簡單,你可以在你支援的所有機器上重複使用編譯器流水線的其餘部分。你基本上是把你的位元組碼作為一種中間程式碼。

Or you can write a virtual machine (VM), a program that emulates a hypothetical chip supporting your virtual architecture at runtime. Running bytecode in a VM is slower than translating it to native code ahead of time because every instruction must be simulated at runtime each time it executes. In return, you get simplicity and portability. Implement your VM in, say, C, and you can run your language on any platform that has a C compiler. This is how the second interpreter we build in this book works.

或者,你可以編寫虛擬機器(VM)8,該程式可在執行時模擬支援虛擬架構的虛擬晶片。在虛擬機器中執行位元組碼比提前將其翻譯成原生代碼要慢,因為每條指令每次執行時都必須在執行時模擬。作為回報,你得到的是簡單性和可移植性。用比如說C語言實現你的虛擬機器,你就可以在任何有C編譯器的平臺上執行你的語言。這就是我們在本書中構建的第二個直譯器的工作原理。

2 . 1 . 8 Runtime

2.1.8 執行時

We have finally hammered the user’s program into a form that we can execute. The last step is running it. If we compiled it to machine code, we simply tell the operating system to load the executable and off it goes. If we compiled it to bytecode, we need to start up the VM and load the program into that.

我們終於將使用者程式錘鍊成可以執行的形式。最後一步是執行它。如果我們將其編譯為機器碼,我們只需告訴作業系統載入可執行檔案,然後就可以運行了。如果我們將它編譯成位元組碼,我們需要啟動VM並將程式載入到其中。

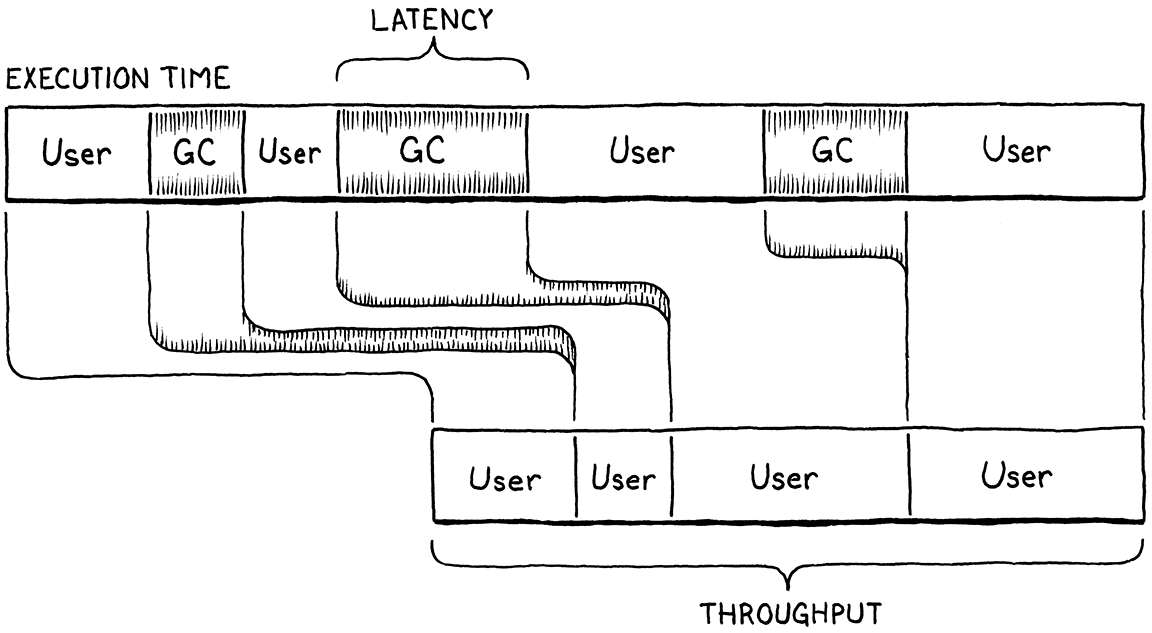

In both cases, for all but the basest of low-level languages, we usually need some services that our language provides while the program is running. For example, if the language automatically manages memory, we need a garbage collector going in order to reclaim unused bits. If our language supports “instance of” tests so you can see what kind of object you have, then we need some representation to keep track of the type of each object during execution.

在這兩種情況下,除了最基本的底層語言外,我們通常需要我們的語言在程式執行時提供一些服務。例如,如果語言自動管理記憶體,我們需要一個垃圾收集器去回收未使用的位元位。如果我們的語言支援用 "instance of "測試我們擁有什麼型別的物件,那麼我們就需要一些表示方法來跟蹤執行過程中每個物件的型別。

All of this stuff is going at runtime, so it’s called, appropriately, the runtime. In a fully compiled language, the code implementing the runtime gets inserted directly into the resulting executable. In, say, Go, each compiled application has its own copy of Go’s runtime directly embedded in it. If the language is run inside an interpreter or VM, then the runtime lives there. This is how most implementations of languages like Java, Python, and JavaScript work.

所有這些東西都是在執行時進行的,所以它被恰當地稱為,執行時。在一個完全編譯的語言中,實現執行時的程式碼會直接插入到生成的可執行檔案中。比如說,在Go中,每個編譯後的應用程式都有自己的一份Go的執行時副本直接嵌入其中。如果語言是在直譯器或虛擬機器內執行,那麼執行時將駐留於虛擬機器中。這也就是Java、Python和JavaScript等大多數語言實現的工作方式。

2 . 2 Shortcuts and Alternate Routes

2.2 捷徑和備選路線

That’s the long path covering every possible phase you might implement. Many languages do walk the entire route, but there are a few shortcuts and alternate paths.

這是一條漫長的道路,涵蓋了你要實現的每個可能的階段。許多語言的確走完了整條路線,但也有一些捷徑和備選路徑。

2 . 2 . 1 Single-pass compilers

2.2.1 單遍編譯器

Some simple compilers interleave parsing, analysis, and code generation so that they produce output code directly in the parser, without ever allocating any syntax trees or other IRs. These single-pass compilers restrict the design of the language. You have no intermediate data structures to store global information about the program, and you don’t revisit any previously parsed part of the code. That means as soon as you see some expression, you need to know enough to correctly compile it.

一些簡單的編譯器將解析、分析和程式碼生成交織在一起,這樣它們就可以直接在解析器中生成輸出程式碼,而無需分配任何語法樹或其他IR。這些單遍編譯器限制了語言的設計。你沒有中間資料結構來儲存程式的全域性資訊,也不會重新訪問任何之前解析過的程式碼部分。 這意味著,一旦你看到某個表示式,就需要足夠的知識來正確地對其進行編譯9。

Pascal and C were designed around this limitation. At the time, memory was so precious that a compiler might not even be able to hold an entire source file in memory, much less the whole program. This is why Pascal’s grammar requires type declarations to appear first in a block. It’s why in C you can’t call a function above the code that defines it unless you have an explicit forward declaration that tells the compiler what it needs to know to generate code for a call to the later function.

Pascal和C語言就是圍繞這個限制而設計的。在當時,記憶體非常珍貴,一個編譯器可能連整個原始檔都無法存放在記憶體中,更不用說整個程式了。這也是為什麼Pascal的語法要求型別宣告要先出現在一個塊中。這也是為什麼在C語言中,你不能在定義函式的程式碼上面呼叫函式,除非你有一個明確的前向宣告,告訴編譯器它需要知道什麼,以便生成呼叫後面函式的程式碼。

2 . 2 . 2 Tree-walk interpreters

2.2.2 樹遍歷直譯器

Some programming languages begin executing code right after parsing it to an AST (with maybe a bit of static analysis applied). To run the program, the interpreter traverses the syntax tree one branch and leaf at a time, evaluating each node as it goes.

有些程式語言在將程式碼解析為AST後就開始執行程式碼(可能應用了一點靜態分析)。為了執行程式,直譯器每次都會遍歷語法樹的一個分支和葉子,並在執行過程中計算每個節點。

This implementation style is common for student projects and little languages, but is not widely used for general-purpose languages since it tends to be slow. Some people use “interpreter” to mean only these kinds of implementations, but others define that word more generally, so I’ll use the inarguably explicit “tree-walk interpreter” to refer to these. Our first interpreter rolls this way.

這種實現風格在學生專案和小型語言中很常見,但在通用語言中並不廣泛使用,因為它往往很慢。有些人使用“直譯器”僅指這類實現,但其他人對“直譯器”一詞的定義更寬泛,因此我將使用沒有歧義的“樹遍歷直譯器”來指代這些實現。我們的第一個直譯器就是這樣工作的10。

2 . 2 . 3 Transpilers

2.2.3 轉譯器

Writing a complete back end for a language can be a lot of work. If you have some existing generic IR to target, you could bolt your front end onto that. Otherwise, it seems like you’re stuck. But what if you treated some other source language as if it were an intermediate representation?

為一種語言編寫一個完整的後端可能需要大量的工作。 如果你有一些現有的通用IR作為目標,則可以將前端轉換到該IR上。 否則,你可能會陷入困境。 但是,如果你將某些其他源語言視為中間程式碼,該怎麼辦?

You write a front end for your language. Then, in the back end, instead of doing all the work to lower the semantics to some primitive target language, you produce a string of valid source code for some other language that’s about as high level as yours. Then, you use the existing compilation tools for that language as your escape route off the mountain and down to something you can execute.

你需要為你的語言編寫一個前端。然後,在後端,你可以生成一份與你的語言級別差不多的其他語言的有效原始碼字串,而不是將所有程式碼降低到某個原始目標語言的語義。然後,你可以使用該語言現有的編譯工具作為逃離大山的路徑,得到某些可執行的內容。

They used to call this a source-to-source compiler or a transcompiler. After the rise of languages that compile to JavaScript in order to run in the browser, they’ve affected the hipster sobriquet transpiler.

人們過去稱之為源到源編譯器或轉換編譯器11。隨著那些為了在瀏覽器中執行而編譯成JavaScript的各類語言的興起,它們有了一個時髦的名字——轉譯器。

While the first transcompiler translated one assembly language to another, today, most transpilers work on higher-level languages. After the viral spread of UNIX to machines various and sundry, there began a long tradition of compilers that produced C as their output language. C compilers were available everywhere UNIX was and produced efficient code, so targeting C was a good way to get your language running on a lot of architectures.

雖然第一個編譯器是將一種組合語言翻譯成另一種組合語言,但現今,大多數編譯器都適用於高階語言。在UNIX廣泛執行在各種各樣的機器上之後,編譯器開始長期以C作為輸出語言。C編譯器在UNIX存在的地方都可以使用,並能生成有效的程式碼,因此,以C為目標是讓語言在許多體系結構上執行的好方法。

Web browsers are the “machines” of today, and their “machine code” is JavaScript, so these days it seems almost every language out there has a compiler that targets JS since that’s the main way to get your code running in a browser.

Web瀏覽器是今天的 "機器",它們的 "機器程式碼 "是JavaScript,所以現在似乎幾乎所有的語言都有一個以JS為目標的編譯器,因為這是讓你的程式碼在瀏覽器中執行的主要方式12。

The front end—scanner and parser—of a transpiler looks like other compilers. Then, if the source language is only a simple syntactic skin over the target language, it may skip analysis entirely and go straight to outputting the analogous syntax in the destination language.

轉譯器的前端(掃描器和解析器)看起來跟其他編譯器相似。 然後,如果源語言只是在目標語言在語法方面的換皮版本,則它可能會完全跳過分析,並直接輸出目標語言中的類似語法。

If the two languages are more semantically different, then you’ll see more of the typical phases of a full compiler including analysis and possibly even optimization. Then, when it comes to code generation, instead of outputting some binary language like machine code, you produce a string of grammatically correct source (well, destination) code in the target language.

如果兩種語言的語義差異較大,那麼你就會看到完整編譯器的更多典型階段,包括分析甚至最佳化。然後,在程式碼生成階段,無需輸出一些像機器程式碼一樣的二進位制語言,而是生成一串語法正確的目標語言的原始碼(好吧,目的碼)。

Either way, you then run that resulting code through the output language’s existing compilation pipeline and you’re good to go.

不管是哪種方式,你再透過目標語言已有的編譯流水線執行生成的程式碼就可以了。

2 . 2 . 4 Just-in-time compilation

2.2.4 即時編譯

This last one is less of a shortcut and more a dangerous alpine scramble best reserved for experts. The fastest way to execute code is by compiling it to machine code, but you might not know what architecture your end user’s machine supports. What to do?

最後一個與其說是捷徑,不如說是危險的高山爭霸賽,最好留給專家。執行程式碼最快的方法是將程式碼編譯成機器程式碼,但你可能不知道你的終端使用者的機器支援什麼架構。該怎麼做呢?

You can do the same thing that the HotSpot JVM, Microsoft’s CLR and most JavaScript interpreters do. On the end user’s machine, when the program is loaded—either from source in the case of JS, or platform-independent bytecode for the JVM and CLR—you compile it to native for the architecture their computer supports. Naturally enough, this is called just-in-time compilation. Most hackers just say “JIT”, pronounced like it rhymes with “fit”.

你可以做和HotSpot JVM、Microsoft的CLR和大多數JavaScript直譯器相同的事情。 在終端使用者的機器上,當程式載入時(無論是JS原始碼還者是平臺無關的JVM和CLR位元組碼),都可以將其編譯為對應的原生代碼,以適應本機支援的體系結構。 自然地,這被稱為即時編譯。 大多數駭客只是說“ JIT”,其發音與“ fit”押韻。

The most sophisticated JITs insert profiling hooks into the generated code to see which regions are most performance critical and what kind of data is flowing through them. Then, over time, they will automatically recompile those hot spots with more advanced optimizations.

最複雜的JIT將效能分析鉤子插入到生成的程式碼中,以檢視哪些區域對效能最為關鍵,以及哪些型別的資料正在流經其中。 然後,隨著時間的推移,它們將透過更高階的最佳化功能自動重新編譯那些熱點部分13。

2 . 3 Compilers and Interpreters

2.3 編譯器和直譯器

Now that I’ve stuffed your head with a dictionary’s worth of programming language jargon, we can finally address a question that’s plagued coders since time immemorial: “What’s the difference between a compiler and an interpreter?”

現在我已經向你的腦袋裡塞滿了一大堆程式語言術語,我們終於可以解決一個自遠古以來一直困擾著程式設計師的問題:編譯器和直譯器之間有什麼區別?

It turns out this is like asking the difference between a fruit and a vegetable. That seems like a binary either-or choice, but actually “fruit” is a botanical term and “vegetable” is culinary. One does not strictly imply the negation of the other. There are fruits that aren’t vegetables (apples) and vegetables that are not fruits (carrots), but also edible plants that are both fruits and vegetables, like tomatoes.

事實證明,這就像問水果和蔬菜的區別一樣。這看上去似乎是一個非此即彼的選擇,但實際上 "水果 "是一個植物學術語,"蔬菜 "是烹飪學術語。嚴格來說,一個並不意味著對另一個的否定。有不是蔬菜的水果(蘋果),也有不是水果的蔬菜(胡蘿蔔),也有既是水果又是蔬菜的可食用植物,比如西紅柿14。

So, back to languages:

- Compiling is an implementation technique that involves translating a source language to some other—usually lower-level—form. When you generate bytecode or machine code, you are compiling. When you transpile to another high-level language you are compiling too.

- When we say a language implementation “is a compiler”, we mean it translates source code to some other form but doesn’t execute it. The user has to take the resulting output and run it themselves.

- Conversely, when we say an implementation “is an interpreter”, we mean it takes in source code and executes it immediately. It runs programs “from source”.

好,回到語言上:

- 編譯是一種實現技術,其中涉及到將源語言翻譯成其他語言——通常是較低階的形式。當你生成位元組碼或機器程式碼時,你就是在編譯。當你移植到另一種高階語言時,你也在編譯。

- 當我們說語言實現“是編譯器”時,是指它會將原始碼轉換為其他形式,但不會執行。 使用者必須獲取結果輸出並自己執行。

- 相反,當我們說一個實現“是一個直譯器”時,是指它接受原始碼並立即執行它。 它“從原始碼”執行程式。

Like apples and oranges, some implementations are clearly compilers and not interpreters. GCC and Clang take your C code and compile it to machine code. An end user runs that executable directly and may never even know which tool was used to compile it. So those are compilers for C.

像蘋果和橘子一樣,某些實現顯然是編譯器,而不是直譯器。 GCC和Clang接受你的C程式碼並將其編譯為機器程式碼。 終端使用者直接執行該可執行檔案,甚至可能永遠都不知道使用了哪個工具來編譯它。 所以這些是C的編譯器。

In older versions of Matz’ canonical implementation of Ruby, the user ran Ruby from source. The implementation parsed it and executed it directly by traversing the syntax tree. No other translation occurred, either internally or in any user-visible form. So this was definitely an interpreter for Ruby.

由 Matz 實現的老版本 Ruby 中,使用者從原始碼中執行Ruby。該實現透過遍歷語法樹對其進行解析並直接執行。期間都沒有發生其他的轉換,無論是在實現內部還是以任何使用者可見的形式。所以這絕對是一個Ruby的直譯器。

But what of CPython? When you run your Python program using it, the code is parsed and converted to an internal bytecode format, which is then executed inside the VM. From the user’s perspective, this is clearly an interpreter—they run their program from source. But if you look under CPython’s scaly skin, you’ll see that there is definitely some compiling going on.

但是 CPython 呢?當你使用它執行你的Python程式時,程式碼會被解析並轉換為內部位元組碼格式,然後在虛擬機器內部執行。從使用者的角度來看,這顯然是一個直譯器——他們是從原始碼開始執行自己的程式。但如果你看一下CPython的內部,你會發現肯定有一些編譯工作在進行。

The answer is that it is both. CPython is an interpreter, and it has a compiler. In practice, most scripting languages work this way, as you can see:

答案是兩者兼而有之。 CPython是一個直譯器,但他也有一個編譯器。 實際上,大多數指令碼語言都以這種方式工作15,如你所見:

That overlapping region in the center is where our second interpreter lives too, since it internally compiles to bytecode. So while this book is nominally about interpreters, we’ll cover some compilation too.

中間那個重疊的區域也是我們第二個直譯器所在的位置,因為它會在內部編譯成位元組碼。所以,雖然本書名義上是關於直譯器的,但我們也會涉及一些編譯的內容。

2 . 4 Our Journey

2.4 我們的旅程

That’s a lot to take in all at once. Don’t worry. This isn’t the chapter where you’re expected to understand all of these pieces and parts. I just want you to know that they are out there and roughly how they fit together.

一下子有太多東西要消化掉。別擔心。這一章並不是要求你理解所有這些零碎的內容。我只是想讓你們知道它們是存在的,以及大致瞭解它們是如何組合在一起的。

This map should serve you well as you explore the territory beyond the guided path we take in this book. I want to leave you yearning to strike out on your own and wander all over that mountain.

當你探索本書本書所指導的路徑之外的領域時,這張地圖應該對你很有用。我希望你自己出擊,在那座山裡到處遊走。

But, for now, it’s time for our own journey to begin. Tighten your bootlaces, cinch up your pack, and come along. From here on out, all you need to focus on is the path in front of you.

但是,現在,是我們自己的旅程開始的時候了。繫好你的鞋帶,背好你的包,走吧。從這裡開始,你需要關注的是你面前的路。

CHALLENGES

習題

1、Pick an open source implementation of a language you like. Download the source code and poke around in it. Try to find the code that implements the scanner and parser. Are they hand-written, or generated using tools like Lex and Yacc? (

.lor.yfiles usually imply the latter.)

1、選擇一個你喜歡的語言的開源實現。下載原始碼,並在其中探索。試著找到實現掃描器和解析器的程式碼,它們是手寫的,還是用Lex和Yacc等工具生成的?(存在.l或.y檔案通常意味著後者)

2、Just-in-time compilation tends to be the fastest way to implement a dynamically-typed language, but not all of them use it. What reasons are there to not JIT?

2、實時編譯往往是實現動態型別語言最快的方法,但並不是所有的語言都使用它。有什麼理由不採用JIT呢?

3、Most Lisp implementations that compile to C also contain an interpreter that lets them execute Lisp code on the fly as well. Why?

3、大多數可編譯為C的Lisp實現也包含一個直譯器,該直譯器還使它們能夠即時執行Lisp程式碼。 為什麼?

-

毫無疑問,CS論文也有死衚衕,被引為零的悲慘小眾論文以及如今被遺忘的最佳化方法,這些最佳化方法只有在以單個位元組為單位來衡量記憶體時才有意義。 ↩

-

我們在本書中構建的語言是動態型別的,因此將在稍後的執行時中進行型別檢查。 ↩

-

有幾種成熟的IR風格。點選你熟悉的搜尋引擎,搜尋 "控制流圖"、"靜態單賦值形式"、"延續傳遞形式 "和 "三位址碼"。 ↩

-

如果你曾經好奇GCC如何支援這麼多瘋狂的語言和體系結構,例如Motorola 68k上的Modula-3,現在你就明白了。 語言前端針對的是少數IR,主要是GIMPLE和RTL。 目標後端如68k,會接受這些IR並生成本機程式碼。 ↩

-

如果你無法抗拒要進入這個領域,可以從以下關鍵字開始,例如“常量摺疊”,“公共表示式消除”,“迴圈不變程式碼外提”,“全域性值編號”,“強度降低”,“ 聚合量標量替換”,“死碼刪除”和“迴圈展開”。 ↩

-

例如,AAD("ASCII Adjust AX Before Division",除法前ASCII調整AX)指令可以讓你執行除法,這聽起來很有用。除了該指令將兩個二進位制編碼的十進位制數字作為運算元打包到一個16位暫存器中。你最後一次在16位機器上使用BCD是什麼時候? ↩

-

這裡的基本原則是,你把特定於體系架構的工作推得越靠後,你就可以在不同架構之間共享更多的早期階段。不過,這裡存在一些矛盾。 許多最佳化(例如暫存器分配和指令選擇)在瞭解特定晶片的優勢和功能時才能發揮最佳效果。 弄清楚編譯器的哪些部分可以共享,哪些應該針對特定目標是一門藝術。 ↩

-

術語“虛擬機器”也指另一種抽象。 “系統虛擬機器”在軟體中模擬整個硬體平臺和作業系統。 這就是你可以在Linux機器上玩Windows遊戲的原因,也是雲提供商為什麼可以給客戶提供控制自己的“伺服器”的使用者體驗,而無需為每個使用者實際分配單獨的計算機。在本書中,我們將要討論的虛擬機器型別是“語言虛擬機器”或“程序虛擬機器”(如果你需要明確的話)。 ↩

-

語法導向翻譯是一種結構化的技術,用於構建這些一次性編譯器。你可以將一個操作與語法的每個片段(通常是生成輸出程式碼的語法片段)相關聯。然後,每當解析器匹配該語法塊時,它就執行操作,一次構建一個規則的目的碼。 ↩

-

一個明顯的例外是早期版本的Ruby,它們是樹遍歷型直譯器。在1.9時,Ruby的規範實現從最初的MRI("Matz' Ruby Interpreter")切換到了Koichi Sasada的YARV("Yet Another Ruby VM")。YARV是一個位元組碼虛擬機器。 ↩

-

第一個轉編譯器XLT86將8080程式集轉換為8086程式集。 這看似簡單,但請記住8080是8位晶片,而8086是16位晶片,可以將每個暫存器用作一對8位暫存器。 XLT86進行了資料流分析,以跟蹤源程式中的暫存器使用情況,然後將其有效地對映到8086的暫存器集。它是由悲慘的電腦科學英雄加里·基爾達爾(Gary Kildall)撰寫的。 他是最早認識到微型計算機前景的人之一,他建立了PL / M和CP / M,這是它們的第一種高階語言和作業系統。 ↩

-

JS曾經是在瀏覽器中執行程式碼的唯一方式。多虧了Web Assembly,編譯器現在有了第二種可以在Web上執行的低階語言。 ↩

-

當然,這正是HotSpot JVM名稱的來源。 ↩

-

花生(連真正的堅果都算不上)和小麥等穀類其實都是水果,但我把這個圖畫錯了。我能說什麼呢,我是個軟體工程師,不是植物學家。我也許應該抹掉這個花生小傢伙,但他太可愛了,我不忍心。 ↩

-

Go工具更是一個奇葩。如果你執行

go build,它就會把你的go原始碼編譯成機器程式碼然後停止。如果你輸入go run,它也會這樣做,然後立即執行生成的可執行檔案。所以,可以說go是一個編譯器(你可以把它當做一個工具來編譯程式碼而不執行);也可以說是一個直譯器(你可以呼叫它立即從原始碼中執行一個程式),並且有一個編譯器(當你把它當做直譯器使用時,它仍然在內部編譯)。 ↩

3.Lox語言 The Lox Language

What nicer thing can you do for somebody than make them breakfast?

——Anthony Bourdain

還有什麼能比給別人做頓早餐,更能體現你對他的好呢?

We’ll spend the rest of this book illuminating every dark and sundry corner of the Lox language, but it seems cruel to have you immediately start grinding out code for the interpreter without at least a glimpse of what we’re going to end up with.

我們將用本書的其餘部分來照亮Lox語言的每一個黑暗和雜亂的角落,但如果讓你在對目標一無所知的情況下,就立即開始為直譯器編寫程式碼,這似乎很殘忍。

At the same time, I don’t want to drag you through reams of language lawyering and specification-ese before you get to touch your text editor. So this will be a gentle, friendly introduction to Lox. It will leave out a lot of details and edge cases. We’ve got plenty of time for those later.

與此同時,我也不想在您編碼之前,就把您拖入大量的語言和規範術語中。所以這是一個溫和、友好的Lox介紹,它會省去很多細節和邊緣情況1。後面我們有足夠的時間來解決這些問題。

3 . 1 Hello, Lox

3 . 1 Hello, Lox

Here’s your very first taste of Lox:

下面是你對Lox的第一次體驗:

// Your first Lox program!

print "Hello, world!";

As that

//line comment and the trailing semicolon imply, Lox’s syntax is a member of the C family. (There are no parentheses around the string because

正如那句//行註釋和後面的分號所暗示的那樣,Lox的語法是C語言家族的成員之一。(因為print是一個內建語句,而不是庫函式,所以字串周圍沒有括號。)

Now, I won’t claim that C has a great syntax. If we wanted something elegant, we’d probably mimic Pascal or Smalltalk. If we wanted to go full Scandinavian-furniture-minimalism, we’d do a Scheme. Those all have their virtues.

這裡,我並不是想說C語言具有出色的語法2。如果我們想要一些優雅的東西,我們可能會模仿Pascal或Smalltalk。如果我們想要完全體現斯堪的納維亞傢俱的極簡主義風格,我們會實現一個Scheme。這些都有其優點。

What C-like syntax has instead is something you’ll find is often more valuable in a language: familiarity. I know you are already comfortable with that style because the two languages we’ll be using to implement Lox—Java and C—also inherit it. Using a similar syntax for Lox gives you one less thing to learn.

但是,類C的語法所具有的反而是一些在語言中更有價值的東西:熟悉度。我知道你已經對這種風格很熟悉了,因為我們將用來實現Lox的兩種語言——Java和C——也繼承了這種風格。讓Lox使用類似的語法,你就少了一件需要學習的事情。

3 . 2 A High-Level Language

3.2 高階語言

While this book ended up bigger than I was hoping, it’s still not big enough to fit a huge language like Java in it. In order to fit two complete implementations of Lox in these pages, Lox itself has to be pretty compact.

雖然這本書最終比我所希望的要大,但它仍然不夠大,無法將Java這樣一門龐大的語言放進去。為了在有限的篇幅裡容納兩個完整的Lox實現,Lox本身必須相當緊湊。

When I think of languages that are small but useful, what comes to mind are high-level “scripting” languages like JavaScript, Scheme, and Lua. Of those three, Lox looks most like JavaScript, mainly because most C-syntax languages do. As we’ll learn later, Lox’s approach to scoping hews closely to Scheme. The C flavor of Lox we’ll build in Part III is heavily indebted to Lua’s clean, efficient implementation.

當我想到那些小而有用的語言時,我腦海中浮現的是像JavaScript3、Scheme和Lua這樣的高階 "指令碼 "語言。在這三種語言中,Lox看起來最像JavaScript,主要是因為大多數c語法語言都是這樣的。稍後我們將瞭解到,Lox的範圍界定方法與Scheme密切相關。 我們將在第三部分中構建的C風格的Lox很大程度上借鑑了Lua的乾淨、高效的實現。

Lox shares two other aspects with those three languages:

Lox與這三種語言有兩個共同之處:

3 . 2 . 1 Dynamic typing

3.2.1 動態型別

Lox is dynamically typed. Variables can store values of any type, and a single variable can even store values of different types at different times. If you try to perform an operation on values of the wrong type—say, dividing a number by a string—then the error is detected and reported at runtime.

Lox是動態型別的。變數可以儲存任何型別的值,單個變數甚至可以在不同時間儲存不同型別的值。如果嘗試對錯誤型別的值執行操作(例如,將數字除以字串),則會在執行時檢測到錯誤並報告。

There are plenty of reasons to like static types, but they don’t outweigh the pragmatic reasons to pick dynamic types for Lox. A static type system is a ton of work to learn and implement. Skipping it gives you a simpler language and a shorter book. We’ll get our interpreter up and executing bits of code sooner if we defer our type checking to runtime.

喜歡靜態型別的原因有很多,但它們都比不上為Lox選擇動態型別的實際原因4。靜態型別系統需要學習和實現大量的工作。跳過它會讓你的語言更簡單,也可以讓本書更短。如果我們將型別檢查推遲到執行時,我們將可以更快地啟動直譯器並執行程式碼。

3 . 2 . 2 Automatic memory management

3.2.2 自動記憶體管理

High-level languages exist to eliminate error-prone, low-level drudgery and what could be more tedious than manually managing the allocation and freeing of storage? No one rises and greets the morning sun with, “I can’t wait to figure out the correct place to call

free()for every byte of memory I allocate today!”

高階語言的存在是為了消除容易出錯的低階工作,還有什麼比手動管理儲存的分配和釋放更繁瑣的呢?沒有人會抬起頭來迎接早晨的陽光,“我迫不及待想找到正確的位置去呼叫free()方法,來釋放掉今天我在記憶體中申請的每個位元組!”

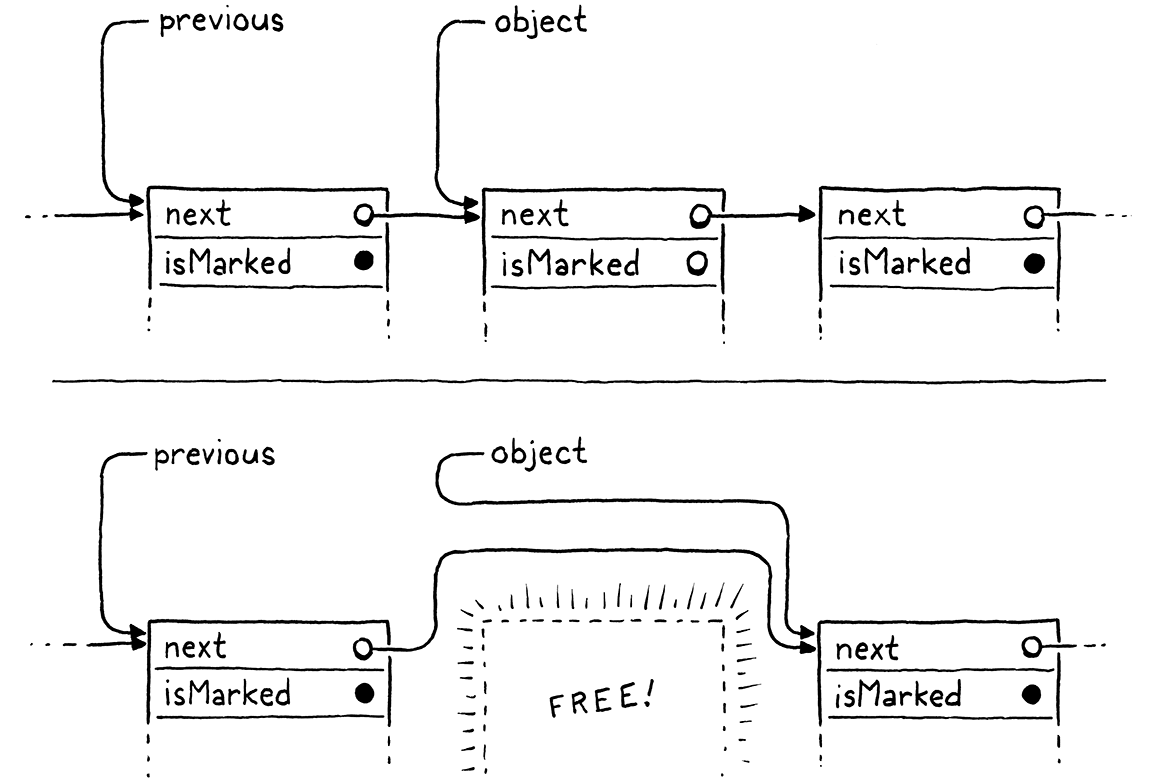

There are two main techniques for managing memory: reference counting and tracing garbage collection (usually just called “garbage collection” or “GC”). Ref counters are much simpler to implement—I think that’s why Perl, PHP, and Python all started out using them. But, over time, the limitations of ref counting become too troublesome. All of those languages eventually ended up adding a full tracing GC or at least enough of one to clean up object cycles.

有兩種主要的記憶體管理技術:引用計數和跟蹤垃圾收集(通常僅稱為“垃圾收集”或“ GC”)5。 引用計數器的實現要簡單得多——我想這就是為什麼Perl、PHP和Python一開始都使用該方式的原因。但是,隨著時間的流逝,引用計數的限制變得太麻煩了。 所有這些語言最終都添加了完整的跟蹤GC或至少一種足以清除物件迴圈引用的管理方式。

Tracing garbage collection has a fearsome reputation. It is a little harrowing working at the level of raw memory. Debugging a GC can sometimes leave you seeing hex dumps in your dreams. But, remember, this book is about dispelling magic and slaying those monsters, so we are going to write our own garbage collector. I think you’ll find the algorithm is quite simple and a lot of fun to implement.

追蹤式垃圾收集是一個聽起來就很可怕的名稱。在原始記憶體的層面上工作是有點折磨人的。除錯GC的時候會讓你在夢中也能看到hex dumps。但是,請記住,這本書是關於驅散魔法和殺死那些怪物的,所以我們要寫出自己的垃圾收集器。我想你會發現這個演算法相當簡單,而且實現起來很有趣。

3 . 3 Data Types

3.3 資料型別

In Lox’s little universe, the atoms that make up all matter are the built-in data types. There are only a few:

在Lox的小宇宙中,構成所有物質的原子是內建的資料型別。只有幾個:

Booleans – You can’t code without logic and you can’t logic without Boolean values. “True” and “false”, the yin and yang of software. Unlike some ancient languages that repurpose an existing type to represent truth and falsehood, Lox has a dedicated Boolean type. We may be roughing it on this expedition, but we aren’t savages.

There are two Boolean values, obviously, and a literal for each one:

Booleans——沒有邏輯就不能編碼,沒有布林值也就沒有邏輯6。 “真”和“假”,就是軟體的陰與陽。 與某些古老的語言重新利用已有型別來表示真假不同,Lox具有專用的布林型別。在這次探險中,我們可能會有些粗暴,但我們不是野蠻人。

顯然,有兩個布林值,每個值都有一個字面量:

true; // Not false.

false; // Not *not* false.

Numbers – Lox only has one kind of number: double-precision floating point. Since floating point numbers can also represent a wide range of integers, that covers a lot of territory, while keeping things simple.

Full-featured languages have lots of syntax for numbers—hexadecimal, scientific notation, octal, all sorts of fun stuff. We’ll settle for basic integer and decimal literals:

Numbers——Lox只有一種數字:雙精度浮點數。 由於浮點數還可以表示各種各樣的整數,因此可以覆蓋很多領域,同時保持簡單。

功能齊全的語言具有多種數字語法-十六進位制,科學計數法,八進位制和各種有趣的東西。 我們只使用基本的整數和十進位制文字:

1234; // An integer.

12.34; // A decimal number.

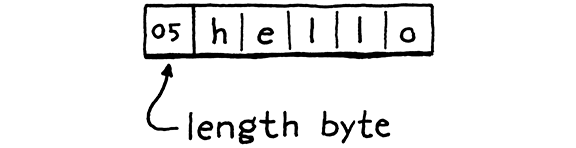

Strings – We’ve already seen one string literal in the first example. Like most languages, they are enclosed in double quotes:

Strings——在第一個示例中,我們已經看到一個字串字面量。 與大多數語言一樣,它們用雙引號引起來:

"I am a string";

""; // The empty string.

"123"; // This is a string, not a number.

As we’ll see when we get to implementing them, there is quite a lot of complexity hiding in that innocuous sequence of characters.

我們在實現它們時會看到,在這個看起來無害的字元序列7中隱藏了相當多的複雜性。

Nil – There’s one last built-in value who’s never invited to the party but always seems to show up. It represents “no value”. It’s called “null” in many other languages. In Lox we spell it

nil. (When we get to implementing it, that will help distinguish when we’re talking about Lox’snilversus Java or C’snull.)There are good arguments for not having a null value in a language since null pointer errors are the scourge of our industry. If we were doing a statically-typed language, it would be worth trying to ban it. In a dynamically-typed one, though, eliminating it is often more annoying than having it.

Nil——還有最後一個內建資料,它從未被邀請參加聚會,但似乎總是會出現。 它代表“沒有價值”。 在許多其他語言中稱為“null”。 在Lox中,我們將其拼寫為nil。 (當我們實現它時,這將有助於區分Lox的nil與Java或C的null)

有一些很好的理由表明在語言中不使用空值是合理的,因為空指標錯誤是我們行業的禍害。如果我們使用的是靜態型別語言,那麼禁止它是值得的。然而,在動態型別中,消除它往往比保留它更加麻煩。

3 . 4 Expressions

3.4 表示式

If built-in data types and their literals are atoms, then expressions must be the molecules. Most of these will be familiar.

如果內建資料型別及其字面量是原子,那麼表示式一定是分子。其中大部分大家都很熟悉。

3 . 4 . 1 Arithmetic

3.4.1 算術運算

Lox features the basic arithmetic operators you know and love from C and other languages:

Lox具備了您從C和其他語言中瞭解到的基本算術運算子:

add + me;

subtract - me;

multiply * me;

divide / me;

The subexpressions on either side of the operator are operands. Because there are two of them, these are called binary operators. (It has nothing to do with the ones-and-zeroes use of “binary”.) Because the operator is fixed in the middle of the operands, these are also called infix operators as opposed to prefix operators where the operator comes before and postfix where it follows the operand.

運算子兩邊的子表示式都是運算元。因為有兩個運算元,它們被稱為二元運算子(這與二進位制的1和0二元沒有關聯)。由於運算子固定在運算元的中間,因此也稱為中綴運算子,相對的,還有字首運算子(運算子在運算元前面)和字尾運算子(運算子在運算元後面)8。

One arithmetic operator is actually both an infix and a prefix one. The

-operator can also be used to negate a number:

有一個數學運算子既是中綴運算子也是字首運算子,-運算子可以對數字取負:

-negateMe;

All of these operators work on numbers, and it’s an error to pass any other types to them. The exception is the

+operator—you can also pass it two strings to concatenate them.

所有這些運算子都是針對數字的,將任何其他型別運算元傳遞給它們都是錯誤的。唯一的例外是+運算子——你也可以傳給它兩個字串將它們串接起來。

3 . 4 . 2 Comparison and equality

3.4.2 比較與相等

Moving along, we have a few more operators that always return a Boolean result. We can compare numbers (and only numbers), using Ye Olde Comparison Operators:

接下來,我們有幾個返回布林值的運算子。我們可以使用舊的比較運算子來比較數字(並且只能比較數字):

less < than;

lessThan <= orEqual;

greater > than;

greaterThan >= orEqual;

We can test two values of any kind for equality or inequality:

我們可以測試兩個任意型別的值是否相等:

1 == 2; // false.

"cat" != "dog"; // true.

Even different types:

即使是不同型別也可以:

314 == "pi"; // false.

Values of different types are never equivalent:

不同型別的值永遠不會相等:

123 == "123"; // false.

I’m generally against implicit conversions.

我通常是反對隱式轉換的。

3 . 4 . 3 Logical operators

3.4.3 邏輯運算

The not operator, a prefix

!, returnsfalseif its operand is true, and vice versa:

取非運算子,是字首運算子!,如果運算元是true,則返回false,反之亦然:

!true; // false.

!false; // true.

The other two logical operators really are control flow constructs in the guise of expressions. An

andexpression determines if two values are both true. It returns the left operand if it’s false, or the right operand otherwise:

其他兩個邏輯運算子實際上是表示式偽裝下的控制流結構。and表示式用於確認兩個運算元是否都是true。如果左側運算元是false,則返回左側運算元,否則返回右側運算元:

true and false; // false.

true and true; // true.

And an

orexpression determines if either of two values (or both) are true. It returns the left operand if it is true and the right operand otherwise:

or表示式用於確認兩個運算元中任意一個(或者都是)為true。如果左側運算元為true,則返回左側運算元,否則返回右側運算元:

false or false; // false.

true or false; // true.

The reason

andandorare like control flow structures is because they short-circuit. Not only doesandreturn the left operand if it is false, it doesn’t even evaluate the right one in that case. Conversely, (“contrapositively”?) if the left operand of anoris true, the right is skipped.

and和 or之所以像控制流結構,是因為它們會短路9。如果左運算元為假,and不僅會返回左運算元,在這種情況下,它甚至不會計算右運算元。反過來,("相對的"?)如果or的左運算元為真,右運算元就會被跳過。

3 . 4 . 4 Precedence and grouping

3.4.4 優先順序與分組

All of these operators have the same precedence and associativity that you’d expect coming from C. (When we get to parsing, we’ll get way more precise about that.) In cases where the precedence isn’t what you want, you can use

()to group stuff:

所有這些運算子都具有與c語言相同的優先順序和結合性(當我們開始解析時,會進行更詳細的說明)。在優先順序不滿足要求的情況下,你可以使用()來分組:

var average = (min + max) / 2;

Since they aren’t very technically interesting, I’ve cut the remainder of the typical operator menagerie out of our little language. No bitwise, shift, modulo, or conditional operators. I’m not grading you, but you will get bonus points in my heart if you augment your own implementation of Lox with them.

我把其他典型的運算子從我們的小語言中去掉了,因為它們在技術上不是很有趣。沒有位運算、移位、取模或條件運算子。我不是在給你打分,但如果你透過自己的方式來完成支援這些運算的Lox實現,你會在我心中得到額外的加分。

Those are the expression forms (except for a couple related to specific features that we’ll get to later), so let’s move up a level.

這些都是表示式形式(除了一些與我們將在後面介紹的特定特性相關的),所以讓我們繼續。

3 . 5 Statements

3.5 語句

Now we’re at statements. Where an expression’s main job is to produce a value, a statement’s job is to produce an effect. Since, by definition, statements don’t evaluate to a value, to be useful they have to otherwise change the world in some way—usually modifying some state, reading input, or producing output.

現在我們來看語句。表示式的主要作用是產生一個值,語句的主要作用是產生一個效果。由於根據定義,語句不求值,因此必須以某種方式改變世界(通常是修改某些狀態,讀取輸入或產生輸出)才能有用。

You’ve seen a couple of kinds of statements already. The first one was:

您已經看到了幾種語句。 第一個是:

print "Hello, world!";

A

print語句計算單個表示式並將結果顯示給使用者10。 您還看到了一些語句,例如:

"some expression";

An expression followed by a semicolon (

;) promotes the expression to statement-hood. This is called (imaginatively enough), an expression statement.

表示式後跟分號(;)可以將表示式提升為語句狀態。這被稱為(很有想象力)表示式語句。

If you want to pack a series of statements where a single one is expected, you can wrap them up in a block:

如果您想將一系列語句打包成一個語句,那麼可以將它們打包在一個塊中:

{

print "One statement.";

print "Two statements.";

}

Blocks also affect scoping, which leads us to the next section…

塊還會影響作用域,我們將在下一節中進行說明。

3 . 6 Variables

3.6 變數

You declare variables using

varstatements. If you omit the initializer, the variable’s value defaults tonil:

你可以使用var語句宣告變數。如果你省略了初始化操作,變數的值預設為nil11:

var imAVariable = "here is my value";

var iAmNil;

Once declared, you can, naturally, access and assign a variable using its name:

一旦宣告完成,你自然就可以透過變數名對其進行訪問和賦值:

var breakfast = "bagels";

print breakfast; // "bagels".

breakfast = "beignets";

print breakfast; // "beignets".

I won’t get into the rules for variable scope here, because we’re going to spend a surprising amount of time in later chapters mapping every square inch of the rules. In most cases, it works like you expect coming from C or Java.

我不會在這裡討論變數作用域的規則,因為我們在後面的章節中將會花費大量的時間來詳細討論這些規則。在大多數情況下,它的工作方式與您期望的C或Java一樣。

3 . 7 Control Flow

3.7 控制流

It’s hard to write useful programs if you can’t skip some code, or execute some more than once. That means control flow. In addition to the logical operators we already covered, Lox lifts three statements straight from C.

如果你不能跳過某些程式碼,或者不能多次執行某些程式碼,就很難寫出有用的程式12。這意味著控制流。除了我們已經介紹過的邏輯運算子之外,Lox直接從C中借鑑了三條語句。

An

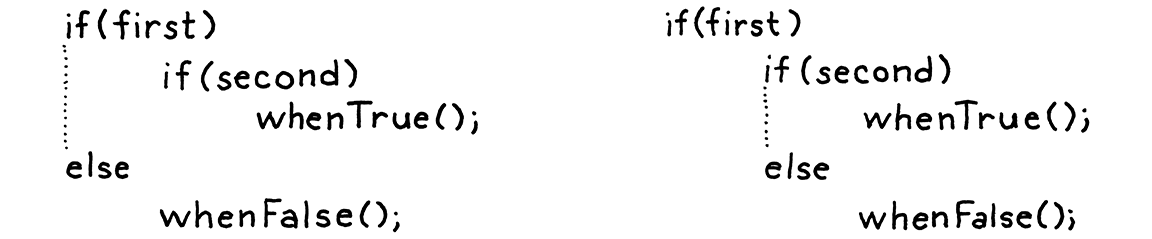

ifstatement executes one of two statements based on some condition:

if語句根據某些條件執行兩條語句中的一條:

if (condition) {

print "yes";

} else {

print "no";

}

A

whileloop executes the body repeatedly as long as the condition expression evaluates to true:

只要條件表示式的計算結果為true,while迴圈就會重複執行迴圈體13:

var a = 1;

while (a < 10) {

print a;

a = a + 1;

}

Finally, we have

forloops:

最後,還有for迴圈:

for (var a = 1; a < 10; a = a + 1) {

print a;

}

This loop does the same thing as the previous

whileloop. Most modern languages also have some sort offor-inorforeachloop for explicitly iterating over various sequence types. In a real language, that’s nicer than the crude C-styleforloop we got here. Lox keeps it basic.

這個迴圈與之前的 while 迴圈做同樣的事情。大多數現代語言也有某種for-in或foreach迴圈,用於顯式迭代各種序列型別14。在真正的語言中,這比我們在這裡使用的粗糙的C-風格for迴圈要好。Lox只保持了它的基本功能。

3 . 8 Functions

3.8 函式

A function call expression looks the same as it does in C:

函式呼叫表示式與C語言中一樣:

makeBreakfast(bacon, eggs, toast);

You can also call a function without passing anything to it:

你也可以在不傳遞任何引數的情況下呼叫一個函式:

makeBreakfast();

Unlike, say, Ruby, the parentheses are mandatory in this case. If you leave them off, it doesn’t call the function, it just refers to it.

與Ruby不同的是,在本例中括號是強制性的。如果你把它們去掉,就不會呼叫函式,只是指向該函式。

A language isn’t very fun if you can’t define your own functions. In Lox, you do that with

fun:

如果你不能定義自己的函式,一門語言就不能算有趣。在Lox裡,你可以透過fun完成:

fun printSum(a, b) {

print a + b;

}

Now’s a good time to clarify some terminology. Some people throw around “parameter” and “argument” like they are interchangeable and, to many, they are. We’re going to spend a lot of time splitting the finest of downy hairs around semantics, so let’s sharpen our words. From here on out:

- An argument is an actual value you pass to a function when you call it. So a function call has an argument list. Sometimes you hear actual parameter used for these.

- A parameter is a variable that holds the value of the argument inside the body of the function. Thus, a function declaration has a parameter list. Others call these formal parameters or simply formals.

現在是澄清一些術語的好時機15。有些人把 "parameter "和 "argument "混為一談,好像它們可以互換,而對許多人來說,它們確實可以互換。我們要花很多時間圍繞語義學來對其進行分辨,所以讓我們在這裡把話說清楚:

- argument是你在呼叫函式時傳遞給它的實際值。所以一個函式呼叫有一個argument列表。有時你會聽到有人用實際引數指代這些引數。

- parameter是一個變數,用於在函式的主體裡面存放引數的值。因此,一個函式宣告有一個parameter列表。也有人把這些稱為形式引數或者乾脆稱為形參。

The body of a function is always a block. Inside it, you can return a value using a

returnstatement:

函式體總是一個塊。在其中,您可以使用return語句返回一個值:

fun returnSum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

If execution reaches the end of the block without hitting a

return, it implicitly returnsnil.

如果執行到達程式碼塊的末尾而沒有return語句,則會隱式返回nil。

3 . 8 . 1 Closures

3.8.1 閉包

Functions are first class in Lox, which just means they are real values that you can get a reference to, store in variables, pass around, etc. This works:

在Lox中,函式是一等公民,這意味著它們都是真實的值,你可以對這些值進行引用、儲存在變數中、傳遞等等。下面的程式碼是有效的:

fun addPair(a, b) {

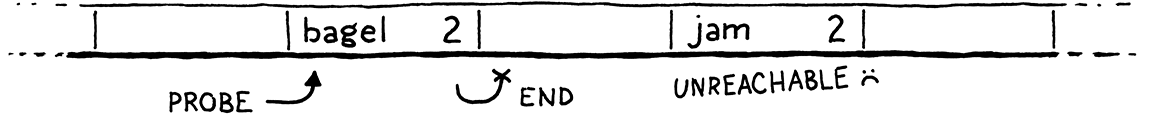

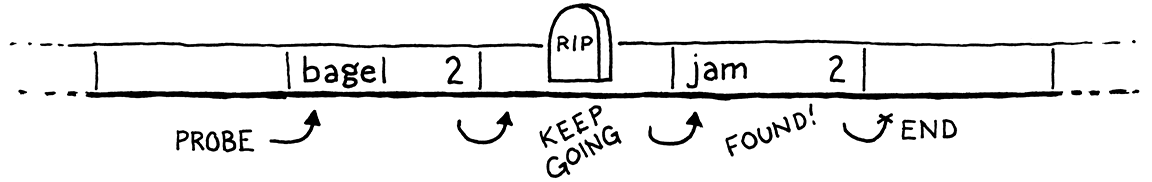

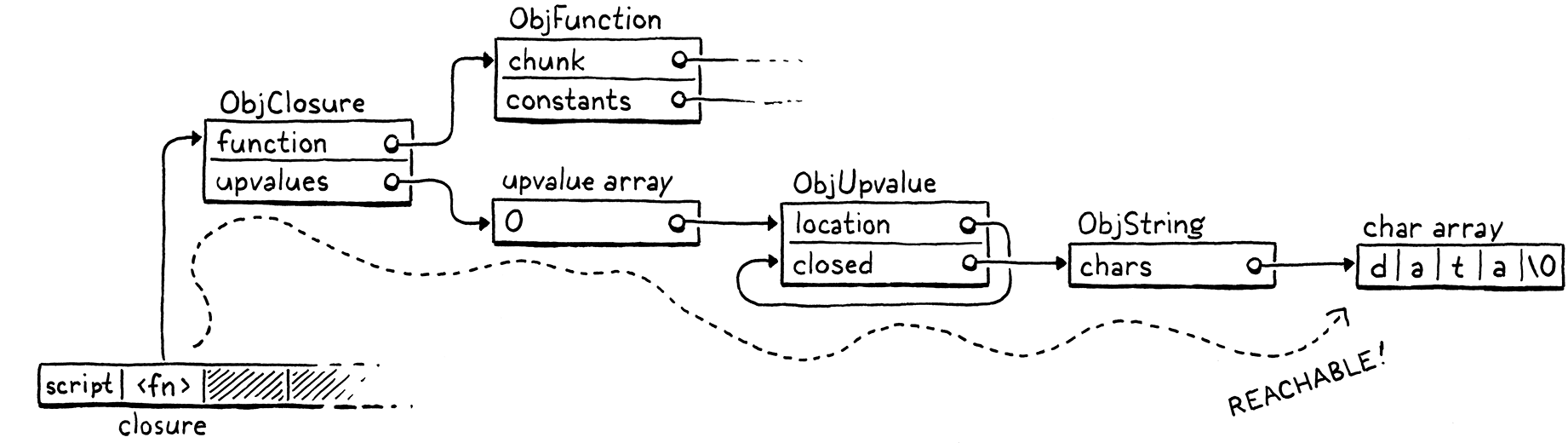

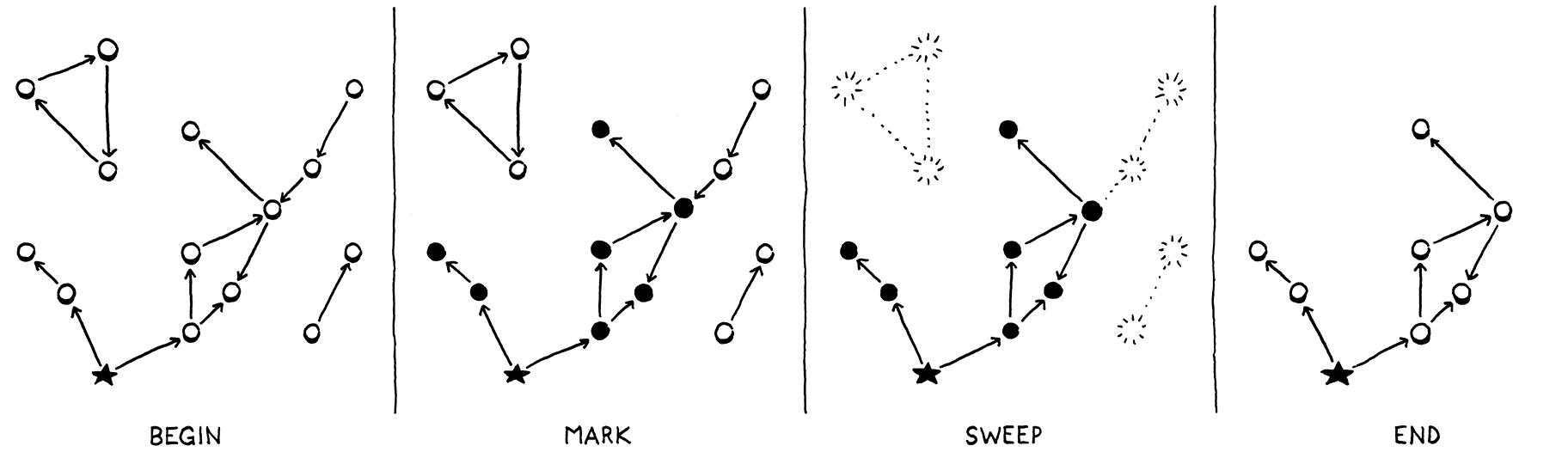

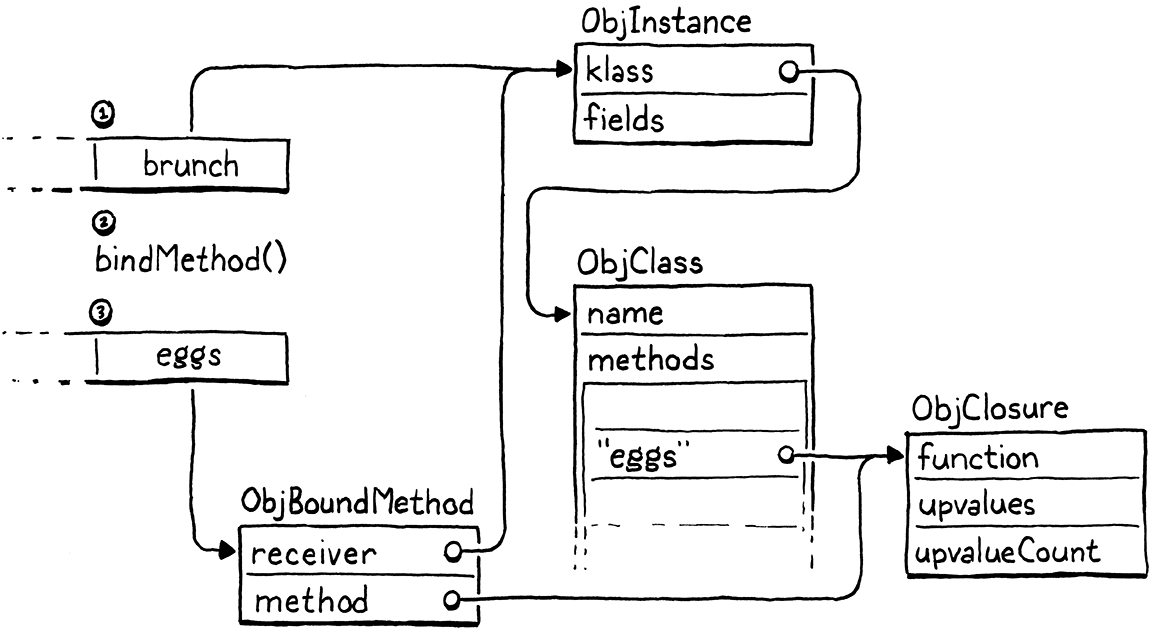

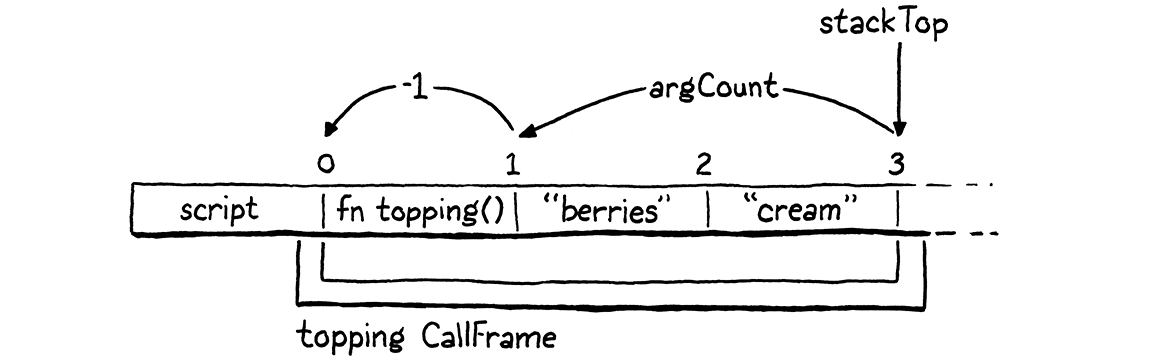

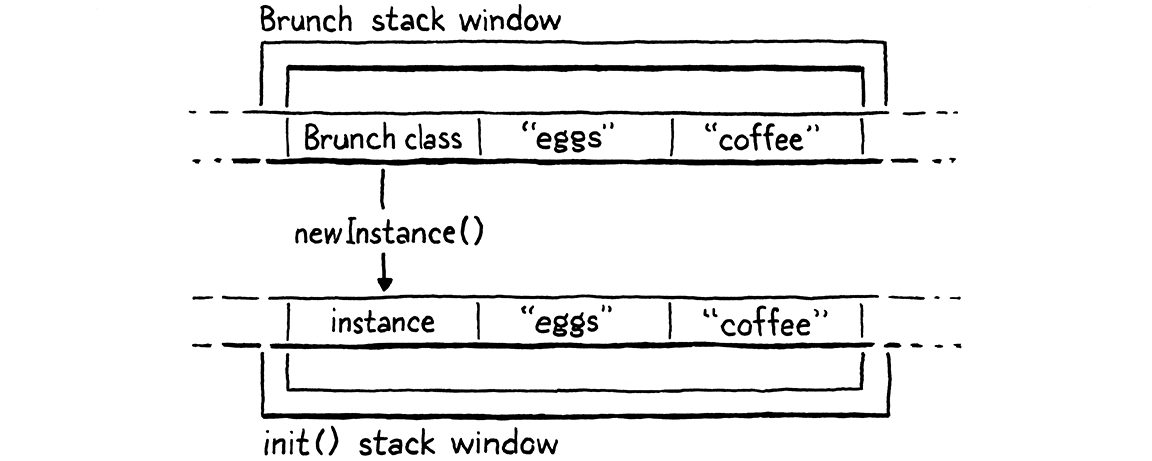

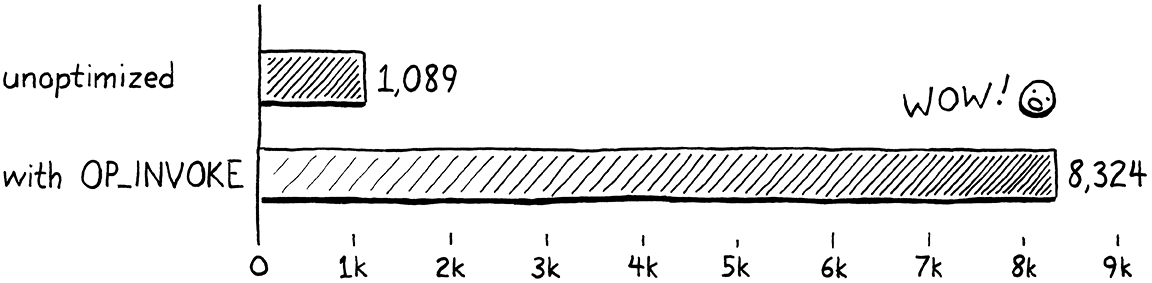

return a + b;